When we commit a wrong, especially after resolving not to, we can become disturbed and discouraged. To atone for our errors and prevent their recurrence, we may want to discipline ourselves. But how do we determine the appropriate level of discipline?

One approach is to distance ourselves from our actions and view ourselves as if we were a person different from us, a person we care for. If that person had committed a lapse similar to ours, how would we respond if they reported it to us? Taking a second-person perspective on ourselves is recommended in the Bhagavad-gita (06.05) when it advises us to elevate ourselves with ourselves — that means we avoid degrading ourselves with self-condemnation and find the best way to help ourselves.

By looking at the misdeeds carefully, we can categorize the underlying motivations into three broad categories: circumstantial, conditional and intentional.

Circumstantially motivated misdeeds: These occur when we succumb to wrongdoing due to extremely provocative or tempting circumstances that we were exposed to or thrust into. Of course, we cannot outsource the responsibility for our actions to the circumstances alone; we need to acknowledge that we played a role in the wrong action or at least agreed to it. However, had we not been exposed to those circumstances, it is unlikely or even improbable that we would have succumbed to wrongdoing. For example, suppose a normally honest person faces a sudden family crisis wherein their loved one’s life is in great danger and they urgently need money for an expensive surgery — and they chance upon an open safe at a friend’s house. They may take money from that safe, but that does not make them a habitual thief ; they soon realize what they did, apologize and make amends. Generally, wrongs committed due to circumstantial motivations are quickly regretted by the wrongdoer, leading them to make reparations — and reform themselves. Such people don’t require too much external disciplining; they are hard enough on themselves.

Conditionally motivated misdeeds: When a person repeatedly engages in wrongdoing, such behavior can’t be attributed to the circumstances alone. Though circumstantial wrongs are usually infrequent, does that mean wrongs that are repetitive are intentional? No, those actions may fall in an intermediate category: conditionally motivated wrongs. Due to their inner conditioning, people may relapse into wrongdoing even without intending to do so. Certainly, their conditioning does not exempt them from responsibility for their wrong actions, yet it does imply that they are not inherently bad or evil. When wrong is done due to conditional reasons, there is repentance for the wrong, but it is not followed by reform because the conditioning is too strong. In such situations, the person may need adequate support and monitoring to both avoid external circumstances that trigger their conditioning and to guard against internal triggers due to which they succumb to their conditionings. The Bhagavad-Gita acknowledges this predicament, outlining in verses 2.60 and 2.67, how people may sometimes be carried away by temptation even against their intelligence and endeavor. Can they overcome their conditioning? Yes, it requires patience, time, and persistence to develop healthier habits for replacing unhealthy habits. By such inner work, they can move from feeling merely repentant to actually becoming reformed.

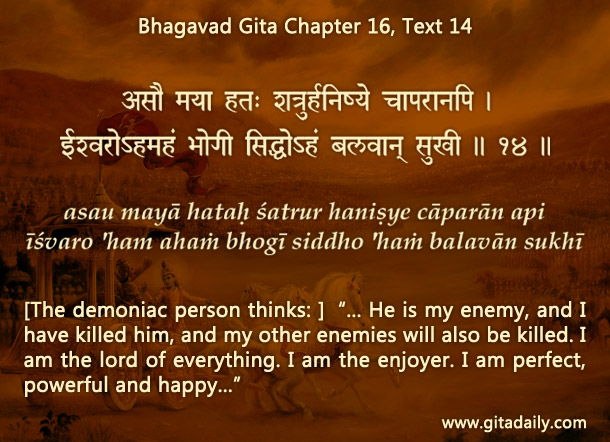

Intentionally motivated misdeeds: These occur when a wrong is committed deliberately, with planned and cynical calculativeness to cover one’s tracks and avoid accountability. Some individuals may scheme to acquire power and position, and use those to do wrong with impunity. Such people may even boast about their so-called cleverness in doing wrong and getting away with it. The Bhagavad-gita (16.13-15) outlines this mentality when describing ungodly people who give themselves completely to lust and anger — and who consider eliminating the opponents as trophies of their own success. Such people feel no repentance and they certainly don’t reform. They can be stopped only by disciplining using appropriate social and legal measures.

Summary:

Not all misdeeds are born equal: misdeeds that are circumstantial are followed by repentance and reform; misdeeds that are conditional are followed by repentance but no reform; misdeeds that are intentional are followed by neither repentance nor reform.

Think it over:

- What characterizes circumstantially motivated misdeeds?

- What characterizes conditionally motivated misdeeds?

- What characterizes intentionally motivated misdeeds?

Audio explanation is here: https://gitadaily.substack.com/p/three-kinds-of-misdeeds

***

16.14: The demoniac person thinks: “… He is my enemy, and I have killed him, and my other enemies will also be killed. I am the lord of everything. I am the enjoyer. I am perfect, powerful and happy.”

To know more about this verse, please click on the image

❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️

Happy to be of service