Whenever we take on a responsible role in our relationships, such as being a parent or mentor, part of that responsibility involves helping others make good choices. Beyond one-off decisions, our goal often extends to fostering their ability to consistently make healthier choices. However, when we see someone repeatedly gravitating toward unhealthy decisions, we might conclude that there’s something broken deep within them. This can compel us to feel a strong calling to fix what’s broken so that they stop breaking themselves.

While such an aspiration is noble, it can easily lead to unintended frustration—both emotionally for ourselves and relationally with those we aim to help. The truth is, we cannot fix others; they must fix what’s broken within themselves. Our role is limited to offering help, which will only be effective to the extent they are willing to appreciate and accept it. If we try to force our help on them, we may come across as controlling, leading to rebellion and defiance. They may reject our guidance, not because it lacks merit but simply to assert their autonomy.

Sometimes, overinvestment in helping others can blur the line between compassion and ego. If their improvement becomes more about proving our capability to fix others than genuinely about their well-being, it can alienate or antagonize them further. They might feel like mere exhibits in our self-centered narrative, reducing the likelihood of meaningful progress.

To address this, we need to fix our mentality about fixing others. By remembering that our role is one of service, not control, we can offer guidance without infringing on their autonomy. Krishna himself exemplifies this approach in the Bhagavad Gita. After sharing his wisdom with Arjuna, Krishna refrains from dictating his decision. Instead, he empowers Arjuna to deliberate and choose his course of action (18.63).

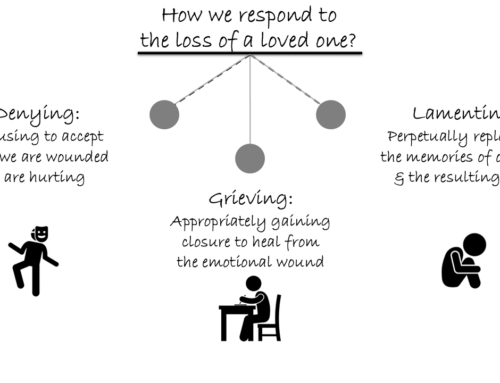

When we balance what we think is good for others with what they feel ready to do, we make our guidance more effective. Incremental steps they take toward improvement can be acknowledged without being derided as signs of incompetence or insincerity. If the time comes to let go because they choose a different path, we can do so gracefully. Such grace leaves the door open for future reconciliation, should they later realize the value of our advice through their own experiences.

An intense desire to help others can stem from genuine compassion. However, when that desire morphs into a compulsive need to control or fix others, it reflects an unhealthy mentality. Recognizing this distinction is crucial for fostering relationships rooted in respect, understanding, and long-term growth.

Summary:

- Taking responsibility for someone naturally involves helping them make healthier choices, but the aspiration to help can sometimes grow into an unhealthy compulsion to fix them.

- A controlling mentality often leads to rebellion and personal frustration when improvement becomes more about proving our capability than focusing on their well-being.

- Following Krishna’s example, we can respect others’ free will, offer resourceful but non-forceful guidance, and let go gracefully when necessary to maintain long-term relationships.

Think it over:

- Reflect on how the desire to help others can go wrong, especially when it transforms into excessive control.

- Recall an experience when you felt controlled and resisted someone’s guidance. How can that inform how you guide others now?

- Consider a current relationship where you are guiding someone. Reflect on how you can offer autonomy and let go gracefully to preserve the long-term bond.

***

18.73 Arjuna said: My dear Kṛṣṇa, O infallible one, my illusion is now gone. I have regained my memory by Your mercy. I am now firm and free from doubt and am prepared to act according to Your instructions.

Leave A Comment