When someone commits a mistake, we often feel as if it is our right and our duty to correct that person. Certainly, many situations call for correction, yet our words of correction frequently don’t have a corrective effect. In fact, quite often, it leads to a counter-productive effect, wherein corrected people go into a hyper-defensive mode, refusing to acknowledge the mistake on their part and indulging in the blame game. Or worse still, they become hostile and alienated, treating us as adversaries and straining our relationship with them.

Correction often backfires thus when our words are insensitively worded. At such times, they act as axes instead of scalpels. Just as axes are often used to bring down whole trees, insensitive correction is often perceived as antagonistic criticism that brings down the other person’s morale or the relationship.

Just as scalpels need to be carefully and expertly handled so that they heal by cutting only the harmful part of the body and not its healthy part, similarly the words of correction need to be carefully and expertly handled so that they heal by cutting only the harmful tendencies of the person and not their healthy morale, their inspiration to perform and drive to achieve.

If an axe were used where a scalpel is needed, it would naturally wreak havoc. Similarly, if our words come off as critical instead of corrective, then they naturally wreak havoc.

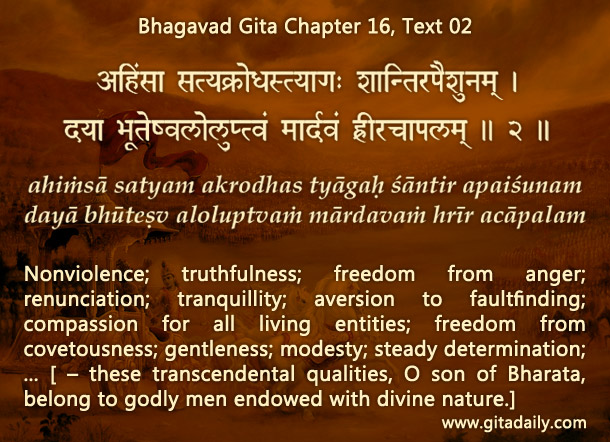

Ensuring that we are corrective, not critical, is not just a matter of changing others’ perception but also of refining our intention. The Bhagavad-gita (17.15) urges us to speak the truth sensitively and pleasingly. And it also (16.02) urges us to cultivate a healthy aversion for faultfinding, wherein we don’t delight in others’ faults and correct them with a caring, not jeering, heart.

Explanation of article:

This is simply wonderful!!!

Hare Krishna!!!

this Gita Daily is like solutions to my everyday question and it specifically addresses the mood of my life on a daily basis, when I am anger or depressed – by the grace of the Supreme personality i read the answers the first thing when I open my email.

Haribol!!!

Hare Krishna Prabhu

The scalpel and Axe analogy is simply far out. It drives the point home. Thank yuo very much for such wonderful easy to understand explanations.

regards

Charudeshna Radhika Dasi

Prabhu,you are the Modern day Krishna to us innumerable Arjunas.I have stopped reading everything else but the Gita daily.