The language issue is becoming increasingly politically polarized in India. For example, what is being perceived as the imposition of Hindi on the rest of the country—especially the southern part—is being fiercely resisted in states like Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu. In this discussion, I will look at language from five different perspectives: functional, cultural, spiritual, political, and educational.

Functional perspective:

Language is probably one of the oldest technologies that humans have developed, and its essential function is communication. This purpose is foundational. For effective communication, three factors matter: our ability to speak a language well, others’ ability to understand it, and the refinement of the language itself in terms of structure, vocabulary, and syntax. Some have tried to promote a single language for all of humanity—perhaps a computer-based language—but such attempts have failed spectacularly. From a functional perspective, English has gained global prominence. In India, Hindi is functionally important as well. However, human beings are not just functional entities.

Cultural perspective:

As the world becomes more interconnected and resembles a global village, many people—especially digital nomads—live more in the digital world than in any fixed physical location. This shift raises concern, even alarm, that cultural markers such as language, which are central to identity, may be lost. For example, the European Union has taken strong steps to preserve local languages despite creating a transnational entity. Similarly, the division of Indian states was done largely along linguistic lines to preserve cultural identity. Especially the mother tongue—the first language learned—remains deeply cherished and must be preserved appropriately.

Spiritual perspective:

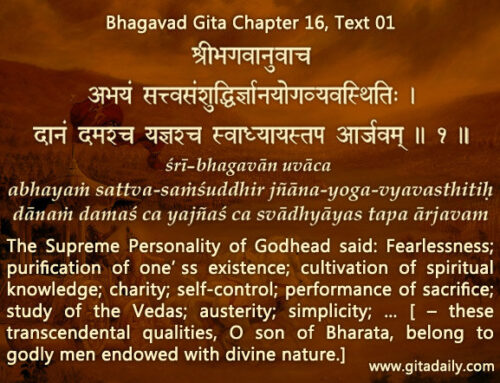

Before we go further into how to preserve languages, it’s important to distinguish cultural from spiritual perspectives. Sometimes cultural identity does not have a spiritual dimension that connects people to higher values or deeper meaning. Spirituality is both cultural and transcultural. In bhakti traditions, for example, spirituality can be expressed in any language. One reason for the rapid spread of spiritual movements across India in medieval times was the vernacularization of sacred compositions like the Ramayana. The popularity of bhakti songs in local languages helped people relate deeply to spiritual ideals. When language is used not only to express who we are, but also who we aspire to become, it acquires a powerful spiritual dimension. In the Ramayana and Mahabharata, language does not appear to be a barrier to establishing dharma. Even when the Pandavas conquered various kingdoms, there is no mention of translators accompanying them. This suggests the presence of an overarching language understood widely, without suppressing local tongues.

Political perspective:

Politically encouraging or facilitating a language to become widespread has been done very successfully by Israel, where Hebrew was revived and is now spoken by thousands. However, India’s sheer diversity and scale make political enforcement of one language a dangerous move. Even with good intentions, such efforts may backfire. Worse, if the intent is political polarization for vote-bank gains, the damage can be deeper. Making language a political issue tends to fail unless a language is widely perceived as vital for survival. Top-down policies rarely succeed. Change emerges best from the bottom up. Even Krishna, though God, does not impose His will on Arjuna in the Bhagavad-gita.

Educational perspective:

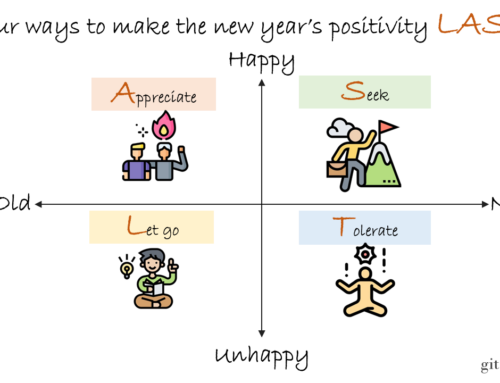

Forcing people to stop using a language in daily life and insisting on another—even through intimidation or violence—does not bring real change. At the educational level, three constructive steps can be taken. First, greater awareness of valuable literature in local languages should be cultivated. Awareness leads to appreciation, which leads to attraction. Second, this is already happening to some extent through the organic growth of regional languages on social media. Third, there must be proper educational infrastructure to support local languages. If all good-quality schools operate only in English or another dominant language, political coercion will not lead to transformation. A holistic, high-level approach rooted in functionality, culture, spirituality, politics, and education can help us move forward meaningfully.

One-Sentence Summary:

The language issue in India demands a holistic, bottom-up approach that respects cultural identity, empowers education, and avoids political coercion.

Think It Over:

1. Why is language both a functional tool and a cultural treasure?

2. How does bhakti spirituality transcend language while also embracing local expressions?

3. What can we learn from Krishna’s non-coercive approach when dealing with cultural or political challenges?

Nice description