When we seek to improve ourselves by developing virtues such as self-control, politeness, or kindness, we often make resolutions that don’t sufficiently translate into transformative actions. We may attribute our failure to our weak willpower, but the problem may lie elsewhere: say, in low clarity about progress.

This is especially true when we are seeking improvement in areas that don’t lend themselves readily to measurement. For example, if we decide to control our anger, we don’t have an anger meter that can easily show us how much we succeeded or failed. And when something is not measured, we tend to live in the domain of guesses or, at best, guesstimates — wherein we may think we are improving when we are actually stagnating or even regressing; or vice versa.

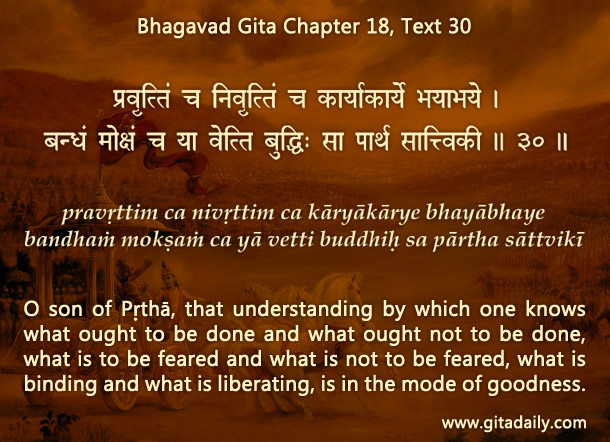

That’s why anything we seek to improve needs to be measured, at least to the degree it can be measured. Significantly, the Bhagavad-gita (18.30) states that intelligence in the mode of goodness discerns between actions that are constructive and actions that are destructive. That means intelligence comes up with appropriate parameters to differentiate between these actions, even if the differentiation is not self-evidently visible or measurable.

For example, we may not be able to quantify our anger, but we can measure how many times we raised our voice above the normal conversational level. Or, we may not be able to measure the quality of our meditation—how much we were absorbed in higher spiritual reality or divinity during our meditation sessions. Yet we can still measure how often we got distracted during our meditation sessions, say by looking at our phone or by talking with someone. And we can also measure the times when we did those sessions, which would indicate how much we prioritize them during our daily schedule and whether we did them during times when we were relatively distraction-free from an external perspective, or we tried to squeeze them in times when we were prone to distraction, especially distractions that were unavoidable due to our other responsibilities.

When we thus devise and use a systematic metric for measurement, we get a clearer picture of where we are going and when we are going in the right direction, how fast we are going. Thus, we can both course-correct if we are going off-track and accelerate if we are going on-track, but too slowly.

That’s why if we are serious about improving something, we need to become serious about measuring whatever aspects of that activity are measurable.

Summary:

That which is not subject to measurement rarely becomes the object of improvement.

Think it over:

- When we fail in our endeavors for self-improvement, what do we often attribute as the cause? Why might that be wrong?

- In evaluating such endeavors, why might we live in the domain of guesstimates?

- List three areas where you would like to improve and list at least one parameter that you can use for measuring your improvement in that area.

***

18.30: O son of Prutha, that understanding by which one knows what ought to be done and what ought not to be done, what is to be feared and what is not to be feared, what is binding and what is liberating, is in the mode of goodness.

Audio explanation of the article is here: https://gitadaily.substack.com/p/why-measurement-matters-for-improvement

To know more about this verse, please click on the image

Leave A Comment