Answer:

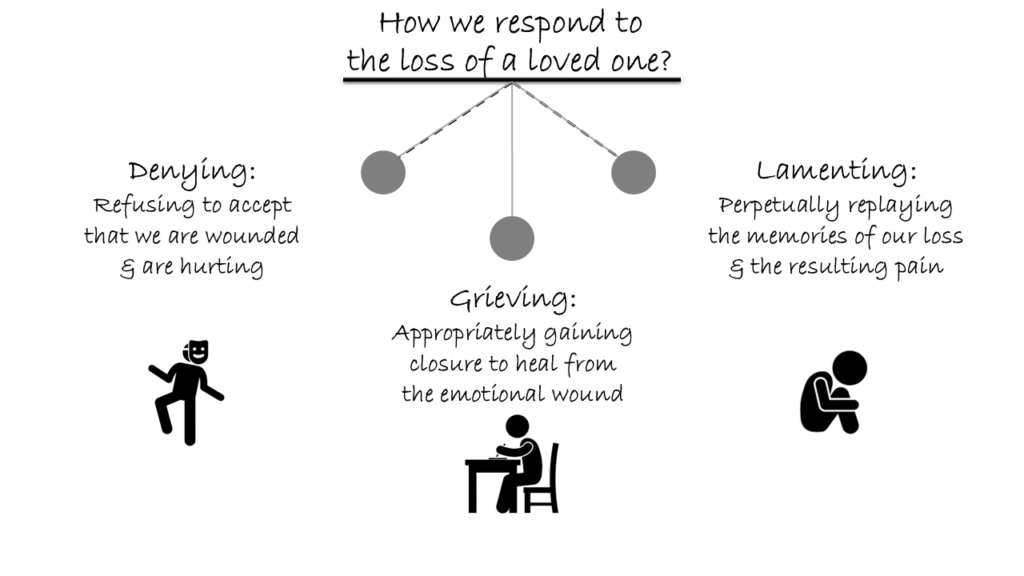

It depends on how the terms are understood. However, if we consider the philosophical context of the wisdom of the Bhagavad-gita, then these two terms have distinct implications. Lamentation has a negative connotation that grief frequently does not. Lamenting involves repeated mental replaying of something bad that has happened and staying emotionally fixated on the resulting negative emotions. When lamenting is used in contrast with grieving, the distressful event is generally the death of someone, leading to severe emotions of distress within a person.

While lamenting is often considered undesirable and unhealthy, grieving is considered, overall, neutral and is often necessary for a person to gain closure at an emotional level after the loss and then to move onward toward emotional healing. Understanding the difference between the two in this sense is important because we may otherwise stay emotionally wounded and may even become emotionally stunted due to the untreated emotional wound’s perpetuating and aggravating.

Emotional wounds and the levels of reality

Whenever we lose someone dear to us, that loss often causes a deep emotional wound within us at the level of our mind, which is generally considered to be the seat of emotions. The Bhagavad-gita explains that we presently exist at three distinct levels of reality: physical, mental, and spiritual. The mind is real and exists at its own level of reality—mental reality—just as the body and the soul are also real and exist at their own respective levels of reality.

Just as a physical wound is a real injury that will bring about real impediments in our functioning, similarly an emotional wound is a real wound at the level of the mind that will bring impediments in our functioning as long as the wound remains. Just as a physical fracture needs to be appropriately treated, an emotional rupture or wound caused by the loss of a loved one has to be appropriately treated.

Denial and lamentation: Two extremes of the pendulum

If we consider the responses to such a loss in the form of a pendulum, one extreme would be denying, wherein we refuse to acknowledge that we are wounded and are in pain. (This denial is different from the denial of refusing to accept that the deceased has actually passed away.)

When there is a physical fracture, there are two distinct phases to the healing. The first is when we put the fractured limb in a sling or cast and avoid moving it. After an adequate period, say a couple of weeks, then the same doctor who told us not to move that limb will then tell us to slowly and incrementally start moving the limb. Otherwise, the limb will atrophy if we don’t move it. Just as not keeping it motionless initially will aggravate the injury, and not moving it eventually will perpetuate the problem due to atrophy, the same two hazards exist with regard to emotional wounds in the form of denying and lamenting.

Grieving as emotional processing and closure

When we have lost a loved one, we need some time to emotionally process the loss. Some people may process that loss through being in isolation and remembering the deceased person, and maybe doing some activity in closure—such as writing down their memories or visiting some place near to them or fulfilling a particular desire that the deceased person had. Others may need to be among close loved ones who are still surviving and be healed through that association. Traditionally, the many rituals involved in performing the last rites of a person who has departed were meant to provide a structure for the healing process. Depending on one’s culture and nature, each person who has suffered a major loss has to find their own way to gain closure.

During the phase of closure, which is like the phase of keeping the hand motionless in the sling or a cast when it has been fractured, one needs to at least partially postpone the normal business of living to focus on processing the loss in whatever way works best for that person. If one doesn’t go through that phase of gaining closure, then the emotional wound may become perpetuated in the sense that the person may become very cold and be afraid to love and care for anyone—or may even become bitter about life itself in its entirety. So such processing of loss is the essence of grieving. It enables healing, whereby one can resume going about the normal business of living.

When grieving turns into lamenting

However, some people may stay on in this phase for not just some days but weeks and months, incessantly replaying the memories of the lost one and doing an endless post-mortem of what led to the loss without arriving at any constructive conclusion. Such unhelpful and even counterproductive fixation of the mind on what has happened in the past is called lamenting. It is like keeping the hand in the sling forever and refusing to ever do any activity, even small, with that hand. Just as there can be physical atrophy due to such inactivity, a person’s entire life can atrophy if they keep lamenting.

Grieving and lamenting through the lens of the gunas

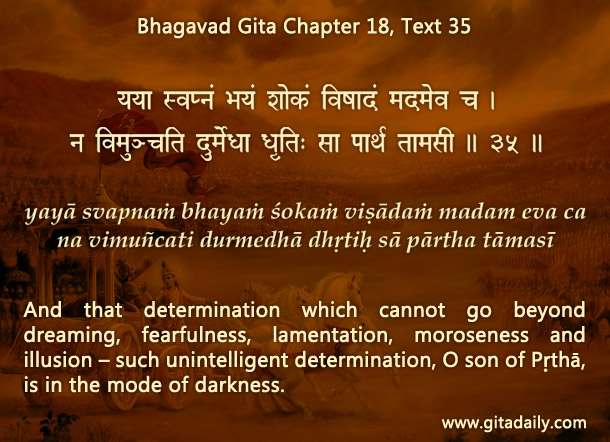

From the perspective of the three modes of material nature, grieving is a natural component of the healing process. When it is done by a person in a constructive way that promotes their healing, it can be said to be in sattva-guna, the mode of goodness. In contrast, lamenting is said to be in the mode of ignorance; this is what the Gita refers to in 2.13 and 18.35. Such lamenting leads to further aggravation of the mode of ignorance in that person. That is, the person becomes increasingly ignorant about the overall nature of life and the ways of coping with life’s inevitable losses and still persevering toward living meaningfully.

***

18.35 And that determination which cannot go beyond dreaming, fearfulness, lamentation, moroseness and illusion – such unintelligent determination, O son of Pṛthā, is in the mode of darkness.

Leave A Comment