Many people think that immoral behavior is ok as long as no one catches them. For example, people from culturally conservative families may think that drinking alcohol is ok as long as their family doesn’t find out. Or with the increasing perception of drinking as a matter of personal preference, not moral principle, they may feel that no one will catch or question them.

Such people consciously or subconsciously redefine morality – not as “doing the right thing”, but as “maintaining the right image, whatever one does.” But their utilitarian redefinition of morality from action to perception doesn’t change the inexorable mechanisms of our inner world. Whenever we do an action repeatedly, every iteration reinforces the mental track for doing it, thereby impelling us to do it again and again. That’s how what starts as a casual titillation (“I enjoy drinking”) can end up as an irresistible addiction (I can’t live without drinking”). Thus people become caught by their sins.

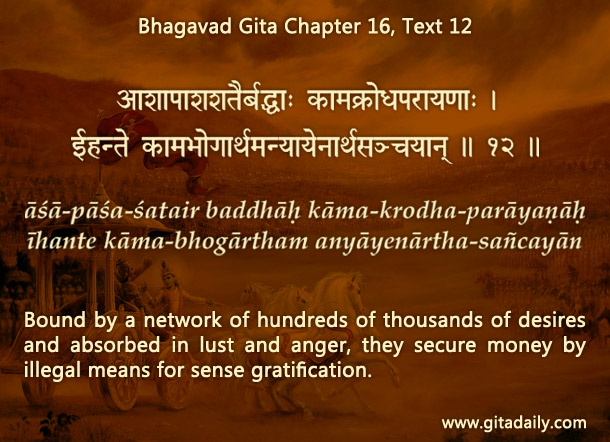

The Bhagavad-gita (16.12) indicates that those who give themselves up to inner inimical drives such as lust and anger are bound by hundreds of noose-like desires. These desires act like tough tight cords that bind their consciousness to their addiction. These bonds, though invisible, function like prisoner’s shackles. They restrict the addicts’ mental freedom, relentlessly dragging their thoughts to their addiction.

Understanding that our choices are self-perpetuating helps us realize that our personal growth depends not on perception but on purification – not on how we look in the world’s eyes, but on how we are in our own heart. This realization inspires us to purify ourselves by practicing bhakti-yoga. When we thus relish higher inner satisfaction, we can resist lower pleasures, thereby breaking free from addiction. Complete purification begets everlasting freedom.

Explanation of article:

Podcast

If you didn’t come here from a daily feed or your daily feed didn’t show a title different from what you see here, then you can neglect this comment.

By mistake, today the same article was posted here as the article posted two days ago. So some of you may have got in your daily feed the following title and the teaser:

*

Context is critical for comprehending content

Posted: 05 Jan 2015 10:49 AM PST

Self-interested people sometimes try to make their questionable opinions seem respectable by quoting esteemed authorities out of context. By such cherry picking, they depict those authorities as saying something different from, even opposite to, what they intended. Such egregious misrepresentation of the Bhagavad-gita is illustrated in some licentious people’s claiming that a sanction for…

*

As soon as I noticed the mistake, I immediately corrected the posting. So now today’s article has been posted in today’s slot – the slot to which today’s daily feed is linked.

That’s why the title in your daily feed and the title on the site may not match – that is, you may click on “context is critical for comprehending content’ and arrive at this article. Rest assured that despite the mismatch, your click has brought you to the right article.

Thank you.

ys

ccdas