Suppose we have a disagreeable neighbor. We can’t evict him, but we don’t have to waste our time quarreling with him. We do the needful to prevent him from damaging our property, but beyond that we just neglect him.

Turn this scenario inwards and we have lust, the disagreeable presence in our consciousness. The Gita (03.40) states that lust resides in our senses, mind and intelligence. From there, it deludes us into believing that sense objects are sources of immense pleasure.

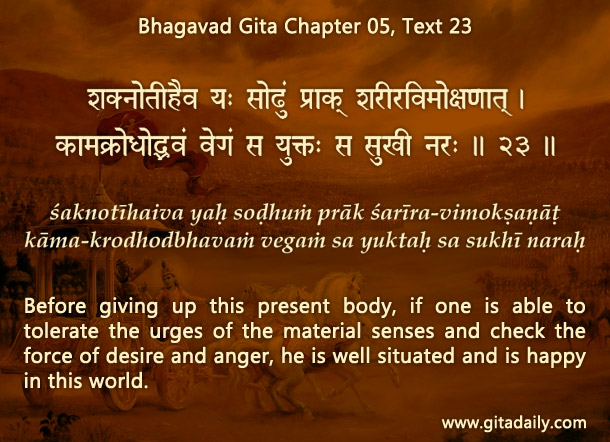

The Gita (05.22) explains how lust’s promises are false: sensual pleasures are temporary – and are trajectories to misery. But even after we intellectually understand why lust’s presence is unwelcome, we can’t drive it out entirely because the impressions from our past sensual indulgence can’t be eradicated overnight. So, the Gita (05.23) recommends that we tolerate lust, that is, endure its presence without succumbing to its influence.

Tolerating lust centers on not paying it any more attention than essential. Whenever it becomes prominent in our consciousness, like the neighbor intruding into our premises, we, using the weapons of Krishna’s wisdom, his name and essentially his remembrance, force it to retreat.

But at other times we focus on keeping ourselves constructively engaged and just neglect lust. In our quest for happiness, we consciously choose as our guide Krishna instead of lust. Being thus guided, we engage in directly devotional activities and re-envision our worldly responsibilities as services to Krishna. By such devotional absorption, we become increasingly purified and connect more deeply with Krishna, who is the reservoir of infinite happiness. Thus, we relish profound spiritual fulfillment, which substantially decreases our craving for sensual pleasures, automatically rendering ineffectual lust’s attempts to allure us. Aptly, the same Gita verse (05.23) assures that tolerating lust and staying engaged in yoga will keep us happy.

Explanation of article:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tRTbwFdEYaI

Leave A Comment