Gita 01.44 – Arjuna’s Reasoning Is Wrong But His Capacity For Reasoning Is Laudable

Audio Link 2: https://www.thespiritualscientist.com/gita-01-44-arjunas-reasoning-is-wrong-but-his-capacity-for-reasoning-is-laudable/

aho bata mahat pāpaṁ

kartuṁ vyavasitā vayam

yad rājya-sukha-lobhena

hantuṁ sva-janam udyatāḥ

Word-for-word:

aho — alas; bata — how strange it is; mahat — great; pāpam — sins; kartum — to perform; vyavasitāḥ — have decided; vayam — we; yat — because; rājya-sukha-lobhena — driven by greed for royal happiness; hantum — to kill; sva-janam — kinsmen; udyatāḥ — trying.

Translation:

Alas, how strange it is that we are preparing to commit greatly sinful acts. Driven by the desire to enjoy royal happiness, we are intent on killing our own kinsmen.

Explanation:

In this verse, Arjuna concludes his argument against fighting in the war, expressing his deep regret:

aho bata mahat pāpaṁ — “Oh, how unfortunate it is that we are about to commit a great sin by destroying our entire dynasty!

kartuṁ vyavasitā vayam — We have all resolved to undertake such a terrible action—how lamentable this is!

yad rājya-sukha-lobhena — Driven by greed for the kingdom and the royal pleasures that come with power,

hantuṁ sva-janam udyatāḥ — we are prepared to destroy our own people.”

Arjuna’s words reveal his inner turmoil, as he contemplates the moral cost of waging war against his own kin purely for the sake of worldly gains.

Before this parva—the Bhīṣma-parva, in which the Bhagavad-gītā appears—the preceding parva was called the Udyoga-parva, thus giving context to the word udyatāḥ (meaning “they were endeavouring”). In the Udyoga-parva, the Pāṇḍavas strived for peace on one hand, and on the other, they sought allies should war become unavoidable. Now, with war imminent, they are ready to fight.

Arjuna, driven by his considerate and compassionate nature, contemplates the terrible consequences of war. At his level of reflection, he concludes that their motivation for fighting is rooted in rājya-sukha-lobhena—greed for royal happiness and the pleasures of sovereignty—which he deems a lamentable motive.

It is interesting that Arjuna uses the word vayam (“we”) in the last several verses. By referring to himself in the plural, Arjuna includes not only himself but also the Pāṇḍavas and, in a sense, Kṛṣṇa, who is listening to him. He conveys a shared responsibility, as if to say, “All of us, all of us Pāṇḍavas—how lamentable it is that we are about to fight a war driven by our greed, and that we are prepared to commit the great sin (mahat pāpaṁ) of killing our own relatives.”

In truth, Arjuna was not motivated by greed, nor were the Pāṇḍavas. If greed had driven them, they would not have endured the thirteen long years of exile. Had they desired the kingdom at any cost, they could have simply rejected the unjust verdict of the rigged gambling match and seized the throne. However, the Pāṇḍavas were honourable—they chose to honor the terms of the gambling match and served their time in the forest as required.

Even after this, they did not display greed for the kingdom. This is evidenced by their willingness to accept Kṛṣṇa’s proposal for a greatly reduced demand, requesting only five villages for them to rule. This acceptance shows that their intentions were not dominated by a desire for power or wealth.

What rājya-sukha (royal pleasure) could come from receiving only five villages for those who had once been celebrated as emperors of the world? Yet the Pāṇḍavas were prepared to be satisfied even with that minimal concession. Although both Kṛṣṇa and the Pāṇḍavas knew that Duryodhana was unlikely to accept the peace proposal, they wanted to show that they had sincerely sought peace. When they ultimately resolved to fight, it was for the cause of justice—not only to reclaim their rightful kingdom but also to seek justice for their dishonoured wife and for the citizens who would otherwise remain at the mercy of a power-hungry, wicked, and envious ruler like Duryodhana. In this sense, their motives were far from greedy. However, at this moment, Arjuna ascribes the motive of greed to himself and, as a result, is filled with lament

We see that greed often drives people to commit terrible acts. History is filled with instances where friends, relatives, and trusted aides conspired against one another for power. One of the most famous examples comes from Shakespeare’s play Julius Caesar, where Caesar’s trusted friend, Brutus, ultimately betrays him. During his struggle against his assassins, when Caesar realizes that Brutus is among them, he exclaims, “You too, Brutus?” This betrayal is so painful that it crushes Caesar’s will to resist, and he loses his spirit to fight.

The point here is that greed for a kingdom—or for any form of power—can turn friends into enemies and brothers into hostile rivals. We often see that a father, a powerful corporate magnate, may pass away, and his sons, instead of honouring his legacy, fight bitterly over his estate. Sometimes this rivalry begins even while the father is still alive. Greed is indeed a destructive force, and the violence it incites, sometimes even to the extent of murder, is horrifying.

Generally, we tend to ascribe evil motives to others, wanting to absolve ourselves by thinking, “I did nothing wrong—they acted this way, so I had to respond as I did.” This mindset often leads us to overlook our own part in a conflict, allowing us to justify our actions without self-reflection.

Although, from the perspective of the philosophy later revealed in the Bhagavad-gītā and Kṛṣṇa’s divine plan, Arjuna’s lamentation here arises from ignorance—both of the bodily conception of life and of Kṛṣṇa’s ultimate purpose. Despite the errors in his specific reasoning, Arjuna’s values are clear—he is unwilling to commit violence merely for the sake of a kingdom. This reluctance shows his deep-seated principles and compassionate nature, even if his understanding is, at this point, incomplete.

Madhusūdana Sarasvatī, a commentator on the Gītā frequently referenced by Viśvanātha Cakravartī Ṭhākura, explains that the purpose of the entire first chapter of the Gītā and the initial eight verses of the second chapter, in which Arjuna speaks, is to highlight his sensitivity, thoughtfulness, considerate and refined nature. These qualities reveal Arjuna as a humane and cultured individual, making him an ideal candidate for spiritual enlightenment.

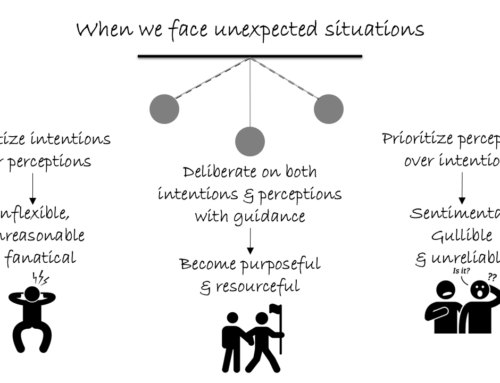

On one level, Arjuna’s ignorance of spiritual knowledge is evident in his arguments, as he is unaware of the transcendental truths that Kṛṣṇa will later reveal. However, on another level, Arjuna is not simply ignorant in the sense of being governed by the mode of ignorance. While he may lack knowledge of the ultimate reality, he is still thinking deeply and reflecting on the situation.

He understands the principles of dharma and the concept that actions have consequences, including the distinctions between pāpa (sin) and puṇya (merit). He knows that actions motivated by greed are detrimental, and he is carefully considering his duties toward his relatives. Based on a thoughtful evaluation of the consequences of his actions, he is attempting to make a decision.

The scriptures are so vast, and their import so profound, that even someone like Arjuna may miss the ultimate conclusion of the scripture. As a result, his reasoning can lead him to a wrong conclusion. However, the capacity for reasoning that he displays here is commendable. Despite being a warrior renowned for his blinding speed and exceptional skill—the champion archer of his time—Arjuna is deeply contemplating the consequences of his actions. This shows his calibre, and it is a calibre that goes beyond mere brute force or skill. It is a calibre of deep thoughtfulness.

Based on this thoughtfulness, the conclusion Arjuna arrives at also demonstrates a remarkable amount of humility. In moments of despair, we often try to shift the blame onto others, attributing the cause of our struggles to external forces. But Arjuna does not say, “The Kauravas caused the war, and it is their greed that is to blame.” Instead, he takes responsibility upon himself, acknowledging his own role in the situation.

In truth, the responsibility does not belong to Arjuna. The cause of the war lies with the Kauravas, not the Pāṇḍavas. Yet, Arjuna is ready to blame himself. If such a mindset were found in a chronically depressed person, where they unnecessarily blame themselves and go into an inferiority complex, it would be unhealthy. However, the capacity for reasoning, the willingness to accept responsibility for one’s actions, and the ability to hold oneself accountable—these are all indicative of a person with strong character.

Arjuna’s strong character will stand him in excellent stead when he receives the spiritual wisdom of the Bhagavad-gītā. With that wisdom, he will be divinely empowered, and his brilliant skill in archery will be used in service to the transcendental Lord, contributing to the welfare of all humanity. In this way, Arjuna demonstrates the qualities of a thoughtful, sensitive, learned, and considerate individual—someone who is truly fit for spiritual enlightenment.

Leave A Comment