Gita 01.43 Hearing Is Important But From Whom We Are Hearing Is Even More Important

Audio Link 1: https://www.thespiritualscientist.com/gita-01-43-hearing-is-important-but-from-whom-we-are-hearing-is-even-more-important/

utsanna-kula-dharmāṇāṁ

manuṣyāṇāṁ janārdana

narake niyataṁ vāso

bhavatīty anuśuśruma

Word-for-word:

utsanna — spoiled; kula-dharmāṇām — of those who have the family traditions; manuṣyāṇām — of such men; janārdana — O Kṛṣṇa; narake — in hell; niyatam — always; vāsaḥ — residence; bhavati — it so becomes; iti — thus; anuśuśruma — I have heard by disciplic succession.

Translation:

O Kṛṣṇa, maintainer of the people, I have heard by disciplic succession that those whose family traditions are destroyed dwell always in hell.

Explanation:

Arjuna has discussed the concept of eternity in different perspectives so far. Earlier, he mentioned how kula-dharmāḥ is sanātanāḥ (Bg 1.39) and kula-dharmāś ca śāśvatāḥ (Bg 1.42), expressing that dynastic duties are long-lasting and eternal. Now, he speaks about how for those who cause the disruption of the dynastic duty—kula-dharmā—the punishment is eternal. He says, narake niyataṁ vāso bhavatīty anuśuśruma: “I have heard from reliable sources that such people will go to hell—and remain in hell forever.”

In the overall context of the Bhagavad-gītā, we see that Arjuna’s words are less about a literal eternal hell and more about a profoundly long, fearsome punishment. He refers to kula-dharmāḥ as sanātanāḥ, but the fact is that kula-dharma is not sanātana because the kula (dynasty) itself is not eternal. A dynasty appears in the material world at a specific time, exists for a certain period, and eventually comes to an end. While it persists for that finite duration, it does not imply that the dynasty is eternal.

In that sense, each of us must consider the individual ramifications of our actions. While reflecting on these ramifications, we need to recognize that the consequences we anticipate will indeed impact us directly. We cannot easily avoid or dismiss those effects.

To deny those effects would be like convincing ourselves that there’s no hope for self-elevation—unless we recognize that certain actions carry serious consequences. Sometimes, the gravity of those consequences needs to be conveyed emphatically. Our actions often tempt us alluringly or goad us insistently, “Do this, do this, do this.” And if we decide to refrain from certain actions, we may still face the challenge of feeling trapped, as we’re unable to fully purge the deepest desires that continue to arise within us.

These deepest desires will, slowly but surely, entrap us. By “deepest,” we mean those intense desires that drag us down into the darkest depths. If we wish to avoid being ensnared in this way, we need to systematically and consistently realign our priorities. Through this realignment, we move toward purification, or at least toward actions that will lead to purification—actions that center on dharma and harmonize with virtue.

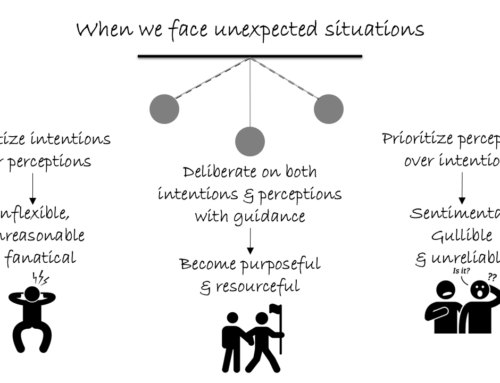

It is interesting that Arjuna points out that this is not merely his opinion but something he has “heard”—bhavatīty anuśuśruma. This highlights that even in hearing, the source matters. Even if we’re hearing from dharmic sources, we may not necessarily be receiving para-dharma; we might instead be absorbing apara-dharma. While apara-dharma (material dharma) is not without value, it isn’t all-important.

Apara-dharma is material religion—religion used as a tool to acquire better things in life. It serves as a means by which each of us can progress towards elevation, liberation, and various forms of progression. However, the elevation and liberation achieved through apara-dharma primarily pertains to material prosperity in terms of dharma, artha, kāma, while mokṣa takes a long time. Even the mokṣa attained in this context is rooted in material consciousness. This is because we still perceive ourselves as products of matter and believe that we must perform certain actions to progress in life. For such progress, we must purge ourselves of negativity.

Hence, one path fosters impiety, while another cultivates piety in the belief that it will bring greater material pleasure. Many Vedic texts address this level of dharma, known as apara-dharma. Listening to such authorities can be uplifting in terms of increasing piety, but it won’t be liberating on a spiritual level. It may still confine us within a certain level of illusion. If we truly seek to avoid being misled in this way, it becomes essential to purify ourselves by choosing to hear from sources that offer genuine spiritual elevation. The Bhagavad-gītā serves as one such source.

Although Arjuna has “heard” from learned authorities, and hearing from such authorities is an authorized way of learning, it is equally important to consider which authorities one listens to. If one hears from karma-kāṇḍa literature, which deals with apara-dharma, one may still be deprived of life’s supreme spiritual benefits. Material benefits may come, but they are transient and not long-lasting.

Through hearing from such sources, Arjuna is now under the misconception of considering the material to be eternal. Whether it is material dharma or the result of material bad karma, here he speaks of eternal hell, but hell itself is not eternal. It is a temporary place, yet Arjuna mistakenly perceives it as eternal, or believes that our residence in hell would be eternal. This belief is often propagated by those who teach us to give up adharma and embrace dharma as a means to help us to, at least by the power of fear, stay on the right path.

Leave A Comment