Whenever things go wrong, finding someone to blame is a default human tendency. When there isn’t anyone clearly to blame, we tend to presume that the perpetrator has cleverly covered their tracks, and we assume we’ll be cleverer to uncover them. Often, our assumptions are already based on whom we dislike. We look for evidence, no matter how inconclusive, to confirm habitual dislike and the resulting default suspicion about that person.

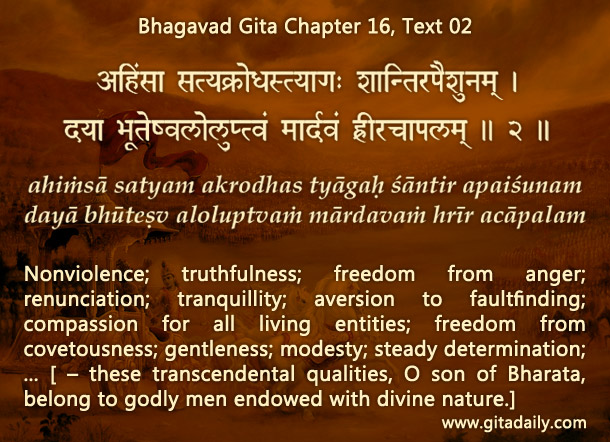

Pertinently, 16.2 declares that an aversion to fault-finding is a characteristic of the godly nature. Such wise people understand two fundamental truths about reality, which must be kept in mind if we are to constructively be a part of the solution and not the problem.

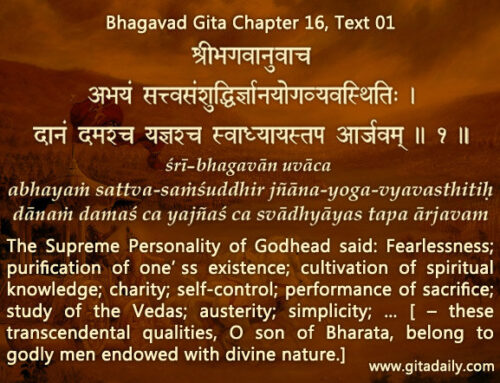

The first truth is that bad things sometimes just happen. We need to be prepared for setbacks because this world is, after all, characterized by distress, as the Bhagavad-Gita (8.15) asserts. The second truth is that finding out exactly why something bad happened is not easy because the intricacies of action are difficult to discern, as the Bhagavad-Gita (4.17) asserts.

Once we keep these twin truths in mind, along with an affinity for and adherence to truth—a characteristic of the godly nature—we can approach problems differently. Rather than asking, “Who is responsible for this mess?” we can direct ourselves with a different question: “Now that this mess has happened, who will be responsible for dealing with it competently and fixing it concretely?”

This shift might deprive us of the quick psychological satisfaction of having someone to blame. It can even bring the anxiety or agony of uncertainty about the problem’s cause. Yet, such a shift can also be empowering, for it opens the door to the opportunity to step forward and volunteer to be a part of the solution.

When things go wrong, people often lose their temper, yelling and throwing things. Adults with childlike minds do the same, though by hurling accusations instead of objects. We can choose to be actual adults in the room.

This is the course of action Arjuna chooses to follow in the Bhagavad-Gita. Rather than fixating on who caused the terrible war he had to fight and letting himself be consumed by vengeful feelings toward the wrongdoers, he focused on taking responsibility to establish a virtuous social and political order that would prevent the recurrence of such injustices and atrocities. More importantly, it would prevent the perpetrators and those with similar mentalities from gaining power again, enabling virtues to survive and thrive. This is the implication of his concluding declaration, expressing his readiness to be an instrument of the divine will (18.73).

Summary:

- Whenever things become messy, we often assume someone caused the mess and tend to blame those we dislike.

- Such a scapegoating mentality is an adult version of a childish mindset that blames others.

- The actual adult doesn’t dwell on the question, “Who is responsible for this mess?” Instead, they ask, “Who will be responsible for fixing this mess?” Empowered by resourcefulness, they become agents of positive change, as did Arjuna at the end of the Gita.

Think It Over:

- What is the default human response whenever things go wrong?

- What are the twin truths that help us not succumb to this default fault-finding mentality?

- What question can we choose to be driven by, and how can it help us deal with messy situations?

***

16.02 Nonviolence; truthfulness; freedom from anger; renunciation; tranquillity; aversion to faultfinding; compassion for all living entities; freedom from covetousness; gentleness; modesty; steady determination; … [– these transcendental qualities, O son of Bharata, belong to godly men endowed with divine nature.]

Leave A Comment