Meditation is essentially about connecting with a timeless divine reality that resides and presides beyond the mundane reality, which is constantly subject to change due to the inexorable force of time. However, meditation is not just an isolated practice; it often comes with a philosophical worldview and a culture. Those who get too caught up in the cultural packaging may find themselves distracted from meditation due to nostalgia or utopia.

Many spiritual cultures talk about a golden age in the past from which humanity has degenerated to its present state of spiritual emptiness and moral directionlessness. Such traditions may also talk about a future golden age when things will be restored to their past glory, or things will be brought to an unprecedented glory in this very world. The cultural packaging may talk about our attaining an ideal world that is free from all the problems that afflict this world.

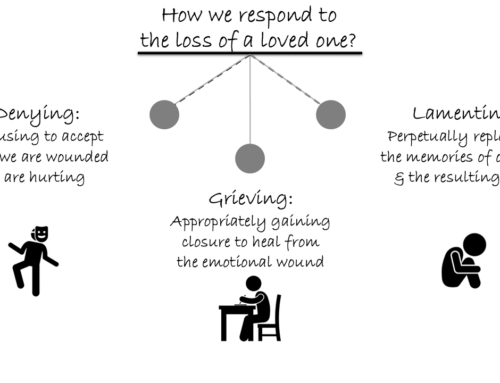

While there is indeed a concrete possibility for the future and a valid aspiration for the present, the expectation that such a perfect state of existence will manifest in this world is undoubtedly utopia. Some people can become enamored by nostalgia or utopia, and some can even become addicted to it, getting completely emotionally consumed by lamenting or resenting the present while compulsively longing for an imagined, idyllic past where meditation was much easier. They hope for the replication of that ideal past in some vague future, where again the externals will be more conducive for them to meditate better.

While conducive externals can help enhance the quality of our meditation, depending on such externals excessively can at best delay our attempts to absorb ourselves in meditation. At worst, it may deflate or even destroy our determination to meditate in the present, in whatever situation we find ourselves.

To prevent such an eventuality, it is vital that we recognize that the past and the future, even if they are infused with spiritual visions or aspirations, can be distractions from the spiritualization of our consciousness in the present. The Bhagavad-gita emphasizes the need for a present-oriented and prioritized consciousness when it declares that serious spiritual seekers neither lament for anything nor hanker for anything. They know that the divine is present in the present, even if the present is unpleasant, and they try to connect with the ever-present divine in the ever-present present.

Summary:

The cultural packaging that comes with meditation practices may sometimes make us disproportionately long for a nostalgic past or a utopian future. While such longings for better externals are understandable, they can become undesirable if they become so compulsive that they distract us from our meditation practice in the present. No matter how unpleasant the present may be, the divine is present in the present, and we need to also be present in the present, meditating and connecting with the all-loving divinity, Krishna.

Think it over:

- Why might meditation practitioners be captivated by the past or the future?

- Why might meditation practitioners long for the past or the future?

- What’s wrong with such longing, and how can it become an obstacle in meditation?

- What insight can protect us from falling for such distracting longings during our meditation?

***

18.54 One who is thus transcendentally situated at once realizes the Supreme Brahman and becomes fully joyful. He never laments or desires to have anything. He is equally disposed toward every living entity. In that state he attains pure devotional service unto Me.

Leave A Comment