Gita 5.4 – See beyond the diversity of process to the commonality of purpose

sāṅkhya-yogau pṛthag bālāḥ

pravadanti na paṇḍitāḥ

ekam apy āsthitaḥ samyag

ubhayor vindate phalam

Word-for-word:

sāṅkhya — analytical study of the material world; yogau — work in devotional service; pṛthak — different; bālāḥ — the less intelligent; pravadanti — say; na — never; paṇḍitāḥ — the learned; ekam — in one; api — even; āsthitaḥ — being situated; samyak — complete; ubhayoḥ — of both; vindate — enjoys; phalam — the result.

Translation

Only the ignorant speak of devotional service [karma-yoga] as being different from the analytical study of the material world [Sāṅkhya]. Those who are actually learned say that he who applies himself well to one of these paths achieves the results of both.

Explanation:

In this verse, Kṛṣṇa answers Arjuna’s question: Which is better—karma-yoga or karma-sannyāsa?

Some confusion may arise because different terms are sometimes used to refer to the same concepts. Here, Kṛṣṇa uses the word “sāṅkhya” to indicate karma-sannyāsa, and the word “yoga” to refer to karma-yoga. This is the same nomenclature He employed in Bhagavad-gītā 3.3 while responding to Arjuna’s query.

Arjuna had earlier asked a similar question about which is better—action or renunciation—and in response, Kṛṣṇa had presented two categories in 3.3:

loke ’smin dvi-vidhā niṣṭhā purā proktā mayānagha

jñāna-yogena sāṅkhyānāṁ karma-yogena yoginām

Jñāna-yogīs, those who renounce action, are referred to by Kṛṣṇa as sāṅkhyānām. Those who perform action with detachment, karma-yogīs, are referred to by Him as yoginām. Thus, Kṛṣṇa employs the same nomenclature here in 5.4.

In this verse, the karma-yogī is referred to by the term yoga, and the karma-sannyāsī is referred to by the term sāṅkhya. Kṛṣṇa states:

sāṅkhya-yogau pṛthag bālāḥ: The idea that the two paths of renunciation and action are different is, according to Him, a childish opinion. Children (bālāḥ) think in this way. While children may possess innocence, they lack discrimination; their intelligence has not yet developed fully. When something is described as a “childish idea,” it implies that it lacks depth and maturity and is based on superficial appearances.

pravadanti na paṇḍitāḥ: The wise do not speak in this way. Why is this so? Because they understand:

ekam apy āsthitaḥ samyag: If a person becomes properly situated in either one of these two paths,

ubhayor vindate phalam: that person attains the result of both.

Here, Kṛṣṇa takes the discussion to a deeper level. The third and fifth chapters share a similar starting point and a similar flow of thought. The analysis follows a comparable pattern, but the concepts and the depth of reasoning in the fifth chapter become far more penetrating.

Here, Kṛṣṇa states that the two paths are not different. One may wonder how this can be, since the processes clearly differ. In sāṅkhya, for example, one gives up action and focuses on contemplation and analysis. Practitioners analyze and deconstruct matter into its fundamental elements, thereby realizing that the charm or captivation of matter is illusory and that one needs to transcend it. This path involves rising to the spiritual level of consciousness through discrimination and the recognition of the illusoriness of material allure.

Therefore, the path of sāṅkhya is one of discrimination and analytical understanding, grounded in contemplation and renunciation of action.

In contrast, the path of yoga—here referring to karma-yoga—is based on action. Therefore, it may appear puzzling how the two can be considered non-different.

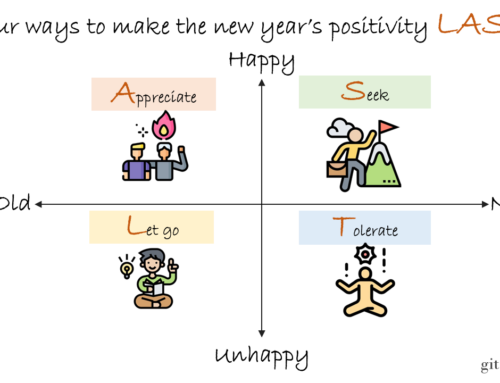

Kṛṣṇa solves this puzzle by explaining that children focus on the differences in the processes, whereas the paṇḍitāḥ, the learned, perceive the commonality of their purpose. Though the two paths differ in their methods, they share the same goal—to transcend matter and realise spirit. Their common purpose is to understand one’s spiritual identity and become firmly situated in spiritual reality.

That is why Kṛṣṇa says here: ekam apy āsthitaḥ—if one becomes properly situated and attains success in one path, then that person attains the fruits of both (ubhayor vindate phalam). This means that the ultimate result of both paths is the same.

To understand this, consider two different approaches for the same purpose—for example, two branches of medicine: allopathy and āyurveda. Their methods of analysis and treatment differ, yet they share a common goal—to restore the patient to health.

Some may question or criticize the merits of the other system. Allopaths may dismiss āyurveda as outdated, unscientific, or impractical, while āyurvedic practitioners may critique allopathy for its side effects, invasiveness, or expense. However, the important point is that these criticisms reflect flaws in the implementation, not the goal itself. People have been successfully treated by both āyurvedic and allopathic medicine.

Hence, the two processes share a common intent. Despite differences in operation and methodology, both lead to the same destination. The means may vary, but the ultimate goal remains identical. Similarly, Kṛṣṇa explains that both sāṅkhya and yoga ultimately guide a person from material consciousness to the supreme spiritual destination.

People with a childish mentality focus on appearances and cannot perceive the underlying substance. That is why they see sāṅkhya and yoga as two entirely different paths. Kṛṣṇa, however, explains that the wise are not misled by outward differences. They perceive the common intent behind both paths, recognizing their essential unity. Therefore, if one becomes properly situated in either path, the person attains the results of both.

Here, Kṛṣṇa is taking the discussion to a deeper level. In the third chapter, when He contrasted karma-yoga and jñāna-yoga, the primary argument was that unqualified practitioners of jñāna-yoga could become hypocrites (mithyācāraḥ sa ucyate); therefore, karma-yoga was recommended. This initial analysis spans verses 3.1 to 3.8.

From 3.9 to 3.16, Kṛṣṇa explains how performing karma-yoga contributes to society and to the cosmic cycle of yajña, thereby setting a proper example. Then, from 3.17 to 3.24, the focus shifts to showing that karma-yoga is preferable because it is beneficial both for society and for Arjuna, according to his personal level of understanding and capacity.

In 5.4, however, Kṛṣṇa is not focusing on the individual level; rather, He is discussing the ultimate destination. Both paths, He emphasizes, lead to the same goal. This is a subtle but very important point. Kṛṣṇa does not merely acknowledge that jñāna-yoga is higher while suggesting that Arjuna may not yet be capable of practicing it. Instead, He asserts that by practicing karma-yoga alone, one can attain perfection.

How exactly karma-yoga leads to perfection or liberation will be discussed in the subsequent flow of this chapter. Understanding this requires seeing how karma-yoga, by the grace of the devotees and the guidance of the guru, can gradually transform into bhakti-yoga, which in turn leads to supreme perfection.

In conclusion, Kṛṣṇa here underscores the point that through the practice of karma-yoga, one can attain the same results as through the practice of sāṅkhya. Therefore, these two paths should not be seen as different; rather, their similarity of purpose should be recognized, and focus should be placed on that common goal.

Thank you.

Leave A Comment