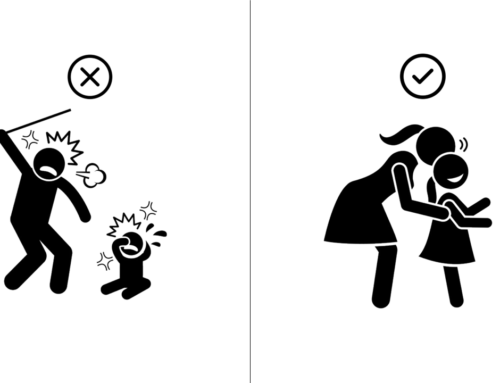

How not to deal with a person whom we consider a necessary evil

Calling someone we dislike but need a “necessary evil” is often an unnecessary evil in itself.

In our social circles, there are often people we dislike. Some of them we can avoid entirely, but others we cannot because we are related to them or need them. We may consider such people necessary evils in our lives. For example, we might find our boss to be demanding and unforgiving and, therefore, dislike or even detest them. Yet, if we need the job, we may try to be courteous on the surface, even if we consider them a necessary evil in our minds or behind their backs.

The problem with such mental labeling and double-handed dealing is that this attitude often leaks through, even against our intentions and without our awareness. Allowing such an attitude to fester in our consciousness can be an unnecessary evil, creating and spreading negativity that may eventually come back to harm us if the person comes to know of our attitude and takes action against us.

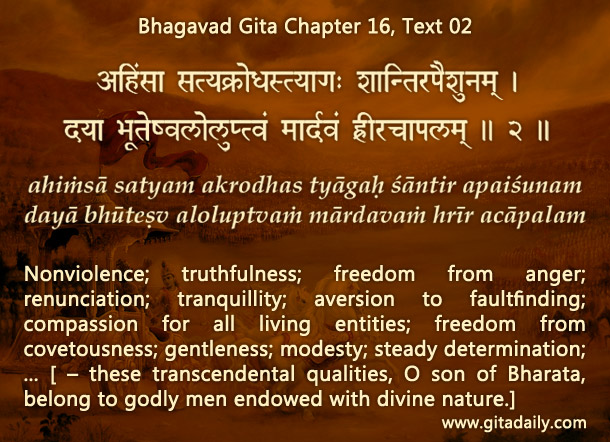

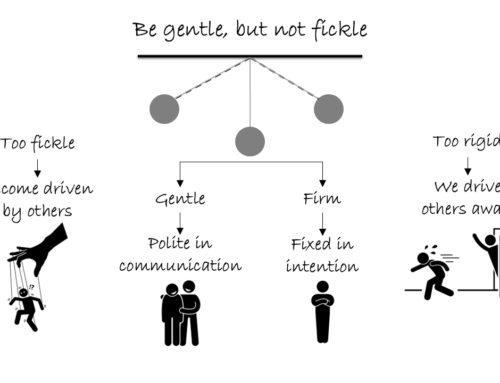

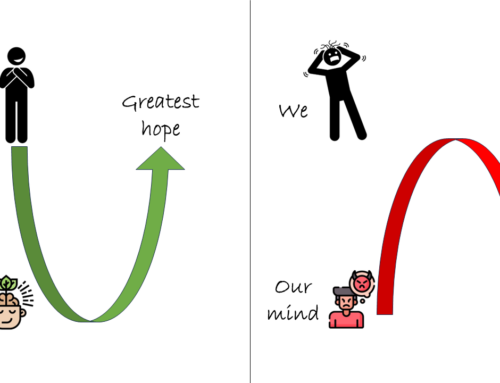

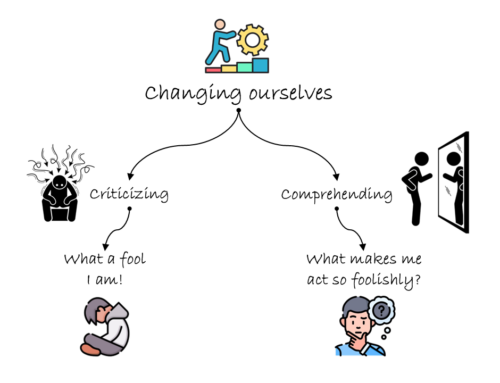

The Bhagavad Gita pertinently urges us to avoid fault-finding (16.2). This doesn’t mean we turn a blind eye to improper behavior or suffer silently due to others’ unpalatable or abusive behavior. It simply means that we shouldn’t be eager to look for the negative in others and that we should try to look for the positive in them. By adopting this disposition, we may find that what we once considered a necessary evil might not be evil at all. Someone we thought of as a necessary evil might be a kind and compassionate person under a hard shell, compelled to act firmly because they are in a responsible role.

Even if we don’t make such a discovery about a particular person, the overall attitude of looking for the good in others will help us avoid unnecessarily antagonizing or alienating people. In the Mahabharata, Duryodhana treated his uncle Vidura as a necessary evil, as Vidura was family and his father was affectionate toward him. But Vidura was not evil at all; he was a well-wisher who had the difficult duty of disciplining Duryodhana—a duty that should have been his father’s, who was unable to do so due to his blind attachment. By treating Vidura as a necessary evil, Duryodhana increased the negativity within himself, leading to his own destruction and the destruction of his dynasty. Such can be the catastrophic cost of seeing only the bad in others, which may lead us to imagine negativity where none exists and bring harm upon ourselves.

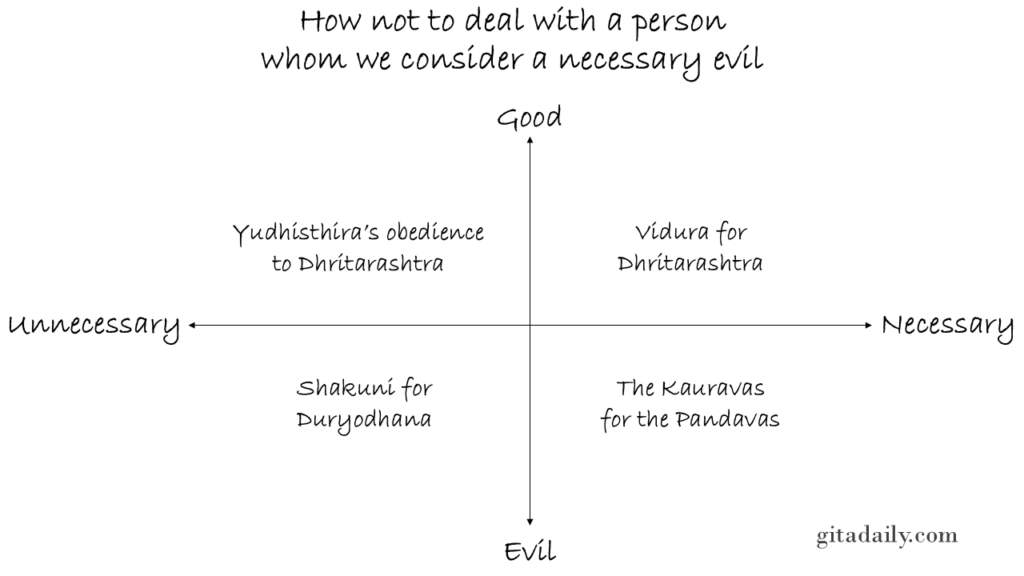

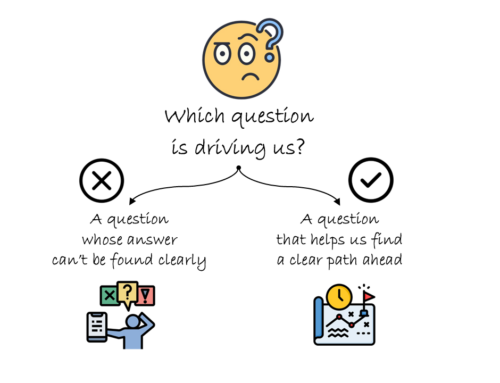

If we consider “necessary” and “evil” as the two axes in a four-quadrant diagram, we can define the quadrants as follows, moving clockwise from the bottom-right:

- Quadrant 1: Necessary Evil

- Quadrant 2: Unnecessary Evil

- Quadrant 3: Unnecessary Good

- Quadrant 4: Necessary Good

This framework can help us understand different types of relationships. While real-life relationships, including those in the Mahabharata, are often multifaceted and messy, and may not always fit neatly into one quadrant, this categorization can provide valuable insights.

Quadrant 1: Necessary Evil

The Pandavas’ relationship with the Kauravas fits here. The Kauravas were their relatives, which made their presence unavoidable—a “necessary evil.” However, when the Kauravas crossed all boundaries by publicly dishonoring Draupadi and insulting Krishna during his peace mission, they became purely evil in the Pandavas’ eyes. This realization led the Pandavas to overlook their familial bond and confront the Kauravas as enemies.

Quadrant 2: Unnecessary Evil

This quadrant represents unnecessary harm or vice, as exemplified by Shakuni’s influence over Duryodhana. Shakuni had no authority over Duryodhana but manipulated him for personal vendetta. Duryodhana’s blind trust in Shakuni led him to commit acts of vice far worse than he might have done on his own.

Quadrant 3: Unnecessary Good

This can be seen in Yudhishthira’s obedience to his blind uncle, Dhritarashtra. Out of deference to his uncle, Yudhishthira agreed to gamble against his will in a rigged match, leading to the loss of his kingdom and exile. Later, Yudhishthira realized that being excessively good to a self-serving person was harmful, and he refused to accept Dhritarashtra’s deceptive peace proposal to remain in exile. This marked his growth in understanding that misplaced goodness can lead to further harm.

Quadrant 4: Necessary Good

The relationship between Vidura and Dhritarashtra illustrates this quadrant. Despite Dhritarashtra rarely heeding Vidura’s advice, Vidura never gave up on his brother. Vidura consistently saw the potential for good within Dhritarashtra and returned to guide him even after being exiled with Dhritarashtra’s silent consent.

After the death of Duryodhana, Dhritarashtra became more open to Vidura’s wisdom. Vidura’s unwavering commitment eventually helped Dhritarashtra attain liberation. Vidura exemplifies a balanced aversion to fault-finding—not by ignoring faults, but by never reducing a person to their faults, allowing room to see their potential for good.

This four-quadrant framework helps us understand how relationships in the Mahabharata reflect nuanced combinations of necessity and morality. By mapping these relationships, we gain a deeper appreciation of their complexity and the lessons they offer for navigating our own relationships.

Summary:

- When dealing with people we don’t like but need, it’s best to be as polite externally and as appreciative as possible internally. Labeling them as necessary evils may invite unnecessary harm by alienating and antagonizing them, as well as by increasing within us the tendency to focus on what is bad in others.

- Looking for the good in others doesn’t mean denying what is bad in them; it simply means we don’t fixate on it and keep the door open to explore whether they might have a softer side beneath their hard shell.

- By doing so, we protect ourselves from the harm that can come from needlessly creating and spreading negativity.

Think it over:

- In dealing with people you don’t like but need, have you ever had a negative attitude toward them that leaked out and created problems?

- Have you ever discovered that a person you considered harsh actually had a soft side that you had failed to see for a long time?

- Focus on one person in your life toward whom you have a negative disposition and contemplate how you might try to see the good within them.

***

16.02 Nonviolence; truthfulness; freedom from anger; renunciation; tranquillity; aversion to faultfinding; compassion for all living entities; freedom from covetousness; gentleness; modesty; steady determination; … [ – these transcendental qualities, O son of Bharata, belong to godly men endowed with divine nature.]

Leave A Comment