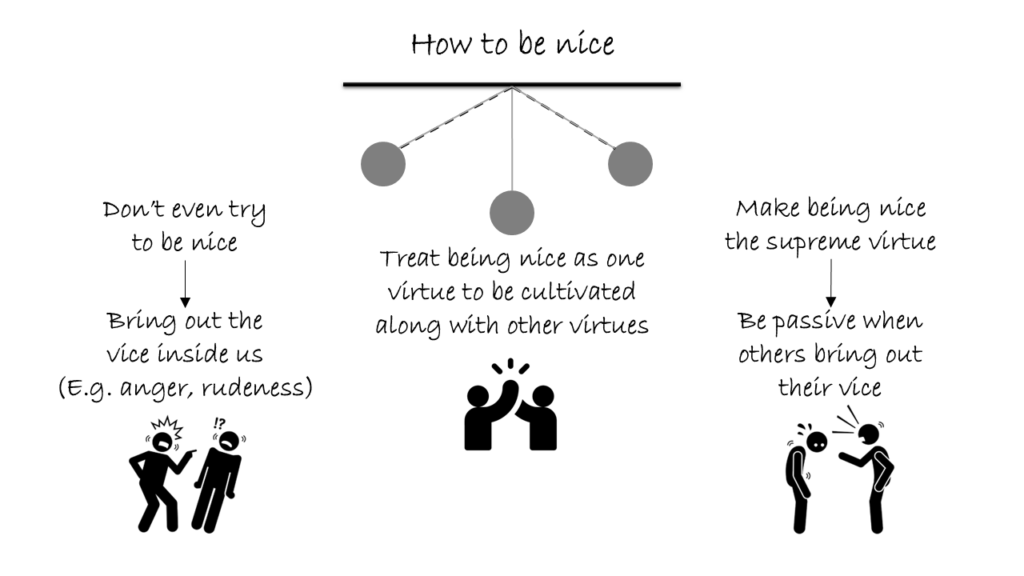

When being nice is not nice…

Be nice to contain the vice that is inside, not to conform to the vice that is outside

Being nice is often considered a hallmark of cultured society. It typically refers to being polite, courteous, and helpful—qualities that are indeed virtuous in the normal course of human interactions. However, when taken to an extreme, being nice can lead to condoning, or even endorsing, immoral or harmful actions. At such times, being nice is not actually nice. Let’s explore this dynamic with an example.

Being nice in personal growth

Imagine a young teenager brought up with healthy values by responsible parents. Upon entering college, he encounters groups with varying behaviors. Based on his upbringing, he chooses to remain calm and polite, avoiding retaliation even when belittled by others. By focusing on his primary purpose—academic growth—he keeps the vice of disruptive emotions, such as anger, in check. Over time, his success silences those who once mocked him.

In this case, being nice helps the teenager contain the vice within himself. This inner control fosters his personal growth and demonstrates the constructive aspect of being nice.

Being nice in the face of wrongdoing

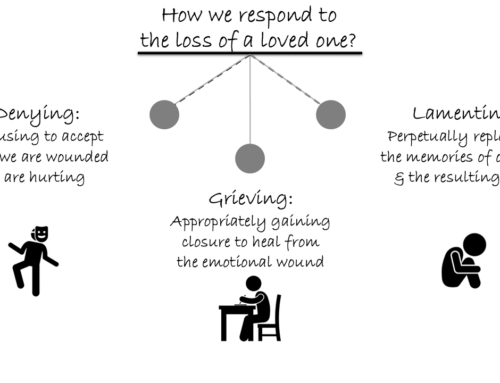

However, suppose the same teenager finds himself in a social circle where peers indulge in delinquent behavior, such as puncturing someone’s bike tires for fun. If, in the name of being nice, he neither opposes their actions nor walks away but instead passively goes along to avoid offending them, his behavior takes a dangerous turn. Over time, his passive condoning may lead to active cheering, and eventually, he might participate in the wrongdoing himself.

In this scenario, being nice results in moral compromise. The teenager becomes not only an enabler but also an accomplice in actions that degrade his character.

Balancing virtues

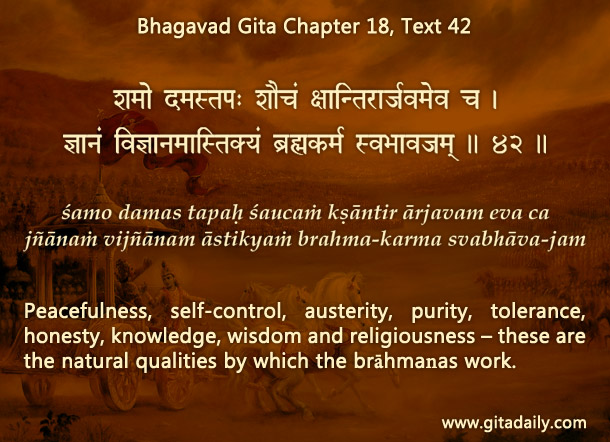

Being nice is not the sole virtue that should define our behavior in every situation. We need to consider other values we cherish and ensure that being nice does not allow vices to take root within us. The Bhagavad-Gita (18.42) provides guidance on this nuanced balance. It describes wise people as self-controlled, non-aggressive in speech, and able to contain vices such as anger or indulgence. This aligns with being nice in the sense of managing internal impulses.

However, the same verse also highlights the importance of being straightforward, which implies not remaining silent or complicit in wrongdoing. Wise individuals balance virtues by making their values clear and standing firm against actions that conflict with those values.

Applying the principle

Understanding that being nice is important but not absolute allows us to ensure that this virtue supports our growth on the path of righteousness. By balancing the virtue of being nice with other principles, we avoid compromising our character and values.

Summary:

- Being nice is beneficial when it helps us contain internal vices and act with courtesy.

- Being nice becomes harmful when it leads us to condone or participate in wrongdoing to avoid appearing impolite.

- By balancing being nice with other virtues, we can ensure it contributes to our growth in character and virtue.

Think it over:

- Reflect on an incident where being nice helped you avoid succumbing to internal vices or destructive urges.

- Recall a situation where excessive prioritization of being nice led you to condone something wrong.

- How can you ensure that being nice supports your growth in virtue without compromising your values?

***

18.42 Peacefulness, self-control, austerity, purity, tolerance, honesty, knowledge, wisdom and religiousness – these are the natural qualities by which the brāhmaṇas work.

Leave A Comment