One of the fundamental implications of the Bhagavad Gita 16.2 directive to be averse to fault-finding is to avoid engaging in rumor-mongering. This means not participating in it or entertaining it but examining rumors carefully whenever we hear or come to know about an allegation—that someone has made a remark or done something questionable, especially when it concerns us or something or someone we care about.

Our default reaction may be to get angry and want to retaliate, but before going into “war mode,” we need a “warning mode” to check if our anger and response are justified. We can evaluate rumors using the acronym R.I.P., which comprises three questions: Is it Real? What does it Imply? What does it Prove? These questions help us rip apart our destructive tendency to misunderstand or overreact.

- Is it Real?

When we receive a message—whether through social media or the grapevine—we should first ask: Did this really happen? Did the person actually say or do what is claimed? Statements can be taken out of context, images and videos can be misrepresented, and even deep fakes can make false claims appear true. We need to verify if what we are reacting to is real before allowing ourselves to become upset.

- What Does it Imply?

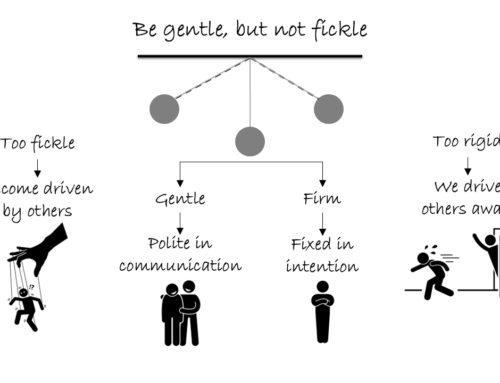

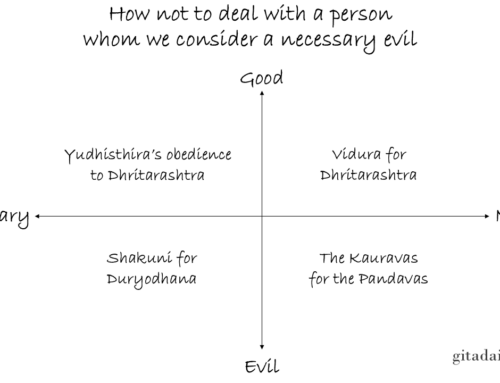

Even if we confirm the truth of the event, we must then ask what it implies. Implications are inferred by the receiver, and these inferences may or may not be valid. For instance, if someone posts an angry message criticizing a group of people, we might assume they are targeting our friend in that group or even indirectly targeting us. This assumption might not be correct. They could be expressing frustration unrelated to us, with their mind focused on entirely different issues. Inference can be intelligent, but assuming implications without proper understanding can signal arrogance or a lack of intelligence.

- What Does it Prove?

Finally, we need to ask: What does this prove? Proof is more objective and tangible than inference. Just because someone makes a critical statement or posts a disapproving message doesn’t mean they are fundamentally prejudiced or hateful. Their action could reflect a moment of weakness, misinformation, or temporary influence by propaganda. Before concluding that the person deserves severe condemnation or cutting off, we should assess whether this act reflects their core character or was an outlier behavior.

By applying these three filters—real, implication, and proof—we can respond to allegations more constructively and avoid unnecessary misunderstandings or overreactions.

Summary:

- When faced with an allegation, first ask: Is this real?

- Then consider: What does it imply? Be careful to differentiate between subjective inferences and actual intentions.

- Finally, evaluate: What does it prove? Ensure not to equate an isolated action with the essence of a person’s character.

Think it over:

- Recall an incident where you assumed an allegation was real without verifying it.

- Do you remember any situation where you or someone you know made an incorrect inference about someone else’s actions?

- Reflect on an instance where certain facts were taken as proof of someone’s character when they were actually just lapses in judgment.

***

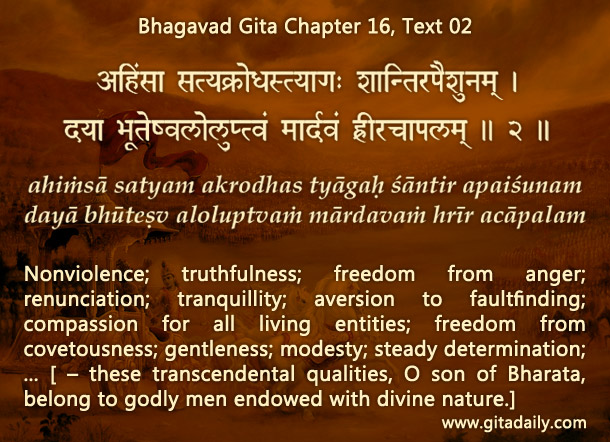

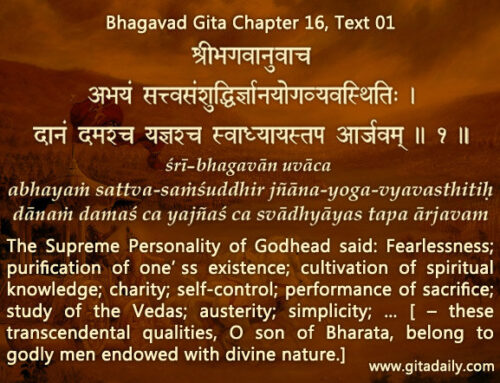

16.02 Nonviolence; truthfulness; freedom from anger; renunciation; tranquillity; aversion to faultfinding; compassion for all living entities; freedom from covetousness; gentleness; modesty; steady determination; … [– these transcendental qualities, O son of Bharata, belong to godly men endowed with divine nature.]

Leave A Comment