To reject an opinion by default just because we dislike the person giving that opinion is just as bad as accepting an opinion just because we like the person giving that suggestion or opinion.

We should base our decisions on evaluating suggestions on merit, not on their source.

Humans are complex creatures, and decision-making is a part of that complex mystery. While we cannot completely demystify or simplify our decision-making process, we can analyze it enough to understand it sufficiently and avoid taking irrational decisions impulsively or rejecting rational suggestions.

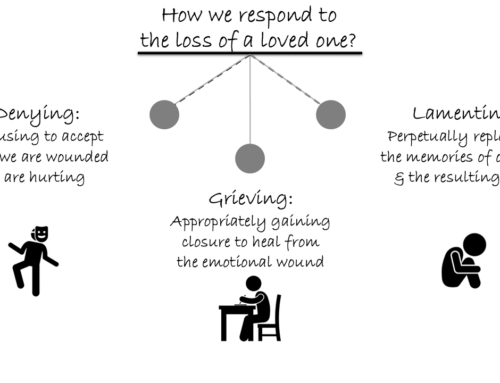

What complicates our decision-making process is the unpredictable and often indecipherable role emotions play. While we are affected by our emotions and should consider them when making decisions, they should not be the basis for decision-making. Why not? Because our emotions can mislead us and make us behave irrationally.

This effect of emotions on our decisions becomes especially evident when dealing with people we strongly like or dislike. Suppose we severely dislike or even detest someone, and we have valid reasons for our negative emotions—perhaps they have said or done terrible things generally or specifically to us. Our emotions will naturally distort our view of that person and substantially, maybe even decisively, affect our response to any suggestion they make.

If we allow our emotions to be the sole basis for decision-making regarding a disliked person’s suggestions, our response may be, “Whatever you say, I disagree with you and reject whatever you say.” Phrased in such absolute terms, we can recognize the absurdity and near derangement of such a response. Even a little common sense reveals our foolishness if we are uncritically outsourcing our decisions, even if reflexively opposing what someone suggests.

To deem a suggestion terrible and rejectable just because it comes from someone we dislike is, in the vision of the Bhagavad-gita, an intelligence or knowledge in the mode of ignorance (18.22). This view reduces a complex issue to one tiny feature.

We can understand the absurdity of such an emotionally driven decision-making approach if we consider the opposite scenario. Suppose we like someone very much and, therefore, unthinkingly accept whatever suggestion they give. Such uncritical acceptance would endanger us, making us vulnerable to “sweet talkers” who may ingratiate themselves with sugary speech, only to mislead us for their benefit and against our own interests.

In the Bhagavad-gita, Krishna, even though he is God and has the greatest wisdom and the greatest well-wishing for us, urges us to deliberate deeply before deciding.

The more we can reduce the monopoly that emotions—our likes or dislikes for someone—have on our responses to their suggestions, the better we will be at accepting good suggestions, even from sources we might usually consider “bad.” This can help us see that people we dislike are not necessarily villains and can make our interactions less acrimonious, contributing to a less polarized and hate-filled world.

Summary:

- Emotions, such as our liking or disliking of someone, can become the sole basis for evaluating their suggestions, which can lead us not only to poor decisions but also to contributing to a more polarized world.

- Intelligence in ignorance misdirects itself by reducing a complex reality to one tiny feature, such as rejecting a suggestion solely because it comes from a disliked person.

- A sounder intelligence evaluates suggestions based on their merit, not on the source or default emotion toward the person making the suggestion.

- Allowing emotions to monopolize decision-making unwittingly gives power over our decisions to others.

Think it over:

- What makes our decision making so complicated?

- Recall a time when you rejected a suggestion impulsively based on who made it and later regretted it.

- How can seeing people’s suggestions without the filter of like or dislike help us become better and contribute to a better world?

***

18.22 And that knowledge by which one is attached to one kind of work as the all in all, without knowledge of the truth, and which is very meager, is said to be in the mode of darkness.

Leave A Comment