Tolerance implies the readiness to live with unpalatable situations. It is a strength that enables us to keep small things small so that we can focus on big things. However, if tolerance is misunderstood or misapplied as passivity, it becomes a weakness.

Suppose someone abuses us, and abuses repeatedly and unrepentantly. If we don’t do anything corrective, not only do we ourselves suffer unbearably, but we also become codependents who perpetuate and aggravate our abuser’s misbehavior. Such abusive behavior sets them up for severe karmic reactions. Being passive amidst abuse hurts both the abused and the abuser.

For tolerance to be a power, not a weakness, we need to practice it in conjunction with a higher purpose. When practiced thus, it empowers us to endure incidental inconveniences without getting distracted. But if something thwarts that purpose itself, then we need to be assertive, not passive.

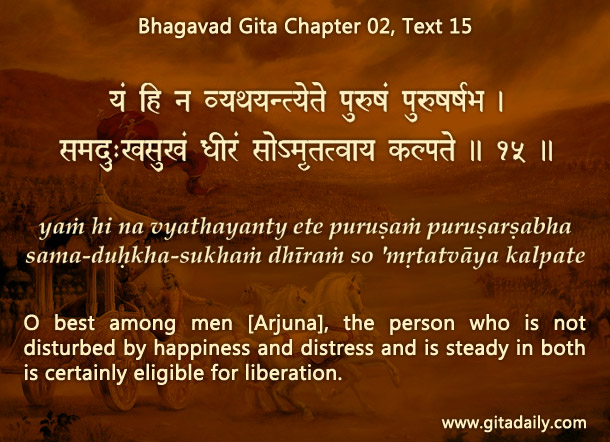

This purposefulness that underlies tolerance is evident in the Bhagavad-gita, which follows up its call for tolerating life’s inevitable ups and downs (02.14) by specifying the desired fruit of tolerance: realization of our transcendental nature as immortal blissful beings (02.15).

The Gita underscores that transcendence, not tolerance, is life’s ultimate end by recommending fighting, the opposite of tolerating. Undoubtedly, such physical war is reserved for exceptional situations when all other options have been exhausted. In the Gita’s context, Arjuna, as a martial guardian of society, had to fight because opposing him were vicious forces who had rejected all efforts for peaceful resolution and who were blocking people’s progress towards transcendence.

In our daily life, we need to fight, not so much against enemies as against inimical situations. By learning to tap the power of tolerance, we can discern which situations to accept and which to alter – while pursuing transcendence through both.

To know more about this verse, please click on the image

Explanation of article:

Podcast:

Leave A Comment