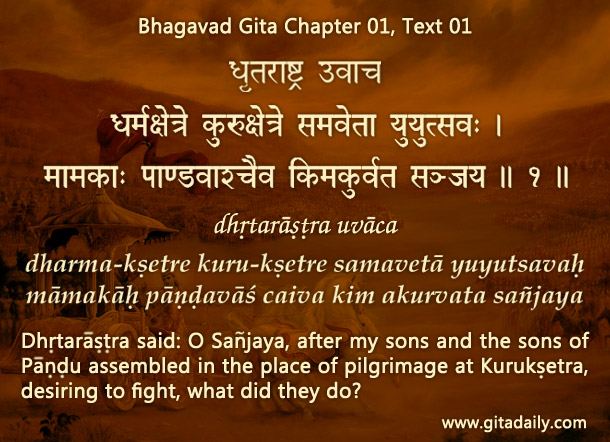

The Bhagavad-gita’s first verse (01.01) can be said to have six key components: dhritarashtra uvaca, dharma-kshetra, kuru-kshetra, samavetah yuyutsavah, mamakah pandavas caiva and kim akurvata. These six components serve a functional purpose by introducing us to the setting. Additionally, each key component also serves a subtler purpose by pointing to the broader themes that will be addressed in the Gita. Let’s look at the significance of the first three components.

Attitudinal significance (dhritarashtra uvaca): Literally, this introduces us to the Gita’s outer narrative framework: a discussion between the blind Kuru king, Dhritarashtra, and his assistant, Sanjaya, who is referred to in this verse’s last word. Dhritarashtra’s ordinary enquiry about events on the battlefield will open for him an unearned opportunity to hear the Gita’s extraordinary wisdom about life’s deepest meaning and highest purpose. But his attachment will obstruct him from appreciating or applying this wisdom. His name, which means attached (dhrita) to kingdom (rashtra), points to the blinding effect of attachments: if we hold too tightly to what we feel is good for us, we deprive ourselves access to what is actually good for us. Thus, the Gita’s first word indirectly alerts us to the attitude that can keep us bereft of its wisdom.

Ethical significance (dharma-kshetra): Literally, dharma-kshetra (the place of dharma) is a describer for the next word, Kuru-kshetra, the place where the Gita is spoken. Additionally, the Gita’s first word conveys its essence — it is a book (kshetra) where the right course of action (dharma) will be explored, established and embraced.

Geographical significance (kuru-kshetra): Literally, this describes the place where the Mahabharata’s climactic battle is to be fought and where the Gita will be spoken. Additionally, this word also conveys the nature of the war: it is meant to be a dharma-yuddha, a war governed by codes of virtuous wars, with the fighting restricted to that particular area and fought only among combatants, with no civilians involved. Because Arjuna soon became unsure whether the war was actually a dharma-yuddha, a war fought for a virtuous purpose, he asked serious questions about dharma (02.07) which led to Krishna speaking the Gita.

Let’s look at the significance of the last three components of the Bhagavad-gita 01.01:

Historical significance (samaveta yuytsavah): Literally, this describes the juncture when the Gita is spoken — after both armies had assembled, ready to fight. Additionally, it suggests that the Gita’s wisdom is of universal relevance throughout history: it is not meant for history buffs interested in a war that happened several thousand years ago; it is meant for responsible individuals facing life’s toughest challenges like wars and seeking philosophical guidelines for judicious action.

Psychological significance (mamakah pandavas caiva): Literally, this is a straightforward enquiry about the actions of the two groups of protagonists on the battlefield — the Kauravas and the Pandavas. Additionally, this also points to the pathological psychology of the speaker, Dhritarashtra. He refers to the Kauravas as his own people, though even the Pandavas were his nephews, and he as the king was meant to treat all his citizens equally, what to speak of his nephews who had lost their father. Dhritarashtra’s word choice unwittingly discloses his partiality that contributed to, if not caused, the catastrophic fratricidal war. For those who want to avoid such blinding attachments, the Gita will offer illuminating wisdom that can inspire spiritual equality and universal solidarity.

Paradoxical significance (kim akurvata): Literally, this can be just an inquiry about events on the battlefield. But it is paradoxical because of the earlier mention of ‘assembled to fight.’ The paradox can be illustrated through a parallel: after they assembled to party, what did they do? The very question suggests an apprehension that what is expected — they partied — might not happen because of some unpredictable factor. That factor might be the vulnerability of the party venue to, say, an extreme weather event such as a rainstorm. In the Gita’s context, that wildcard is dharma-kshetra, the place is celebrated for its long history of past virtuous activities. Dhritarashtra feared that the place’s influence might affect his impious son negatively, given that Duryodhana was a recalcitrant violator of dharma. Significantly, the place did have an unexpected bearing on events — Duryodhana didn’t feel prompted to act according to dharma, but Arjuna felt driven to enquire urgently about dharma, thereby leading to the revelation of the Gita, which is a dharma-shastra (a sacred book about dharma)

To know more about this verse, please click on the image

Leave A Comment