Gita 01.45 – Sound Arguments From A Fragmented Perception Are Actually Unsound

Audio Link 2: https://www.thespiritualscientist.com/gita-01-45-sound-arguments-from-a-fragmented-perception-are-actually-unsound/

yadi mām apratīkāram

aśastraṁ śastra-pāṇayaḥ

dhārtarāṣṭrā raṇe hanyus

tan me kṣema-taraṁ bhavet

Word-for-word:

yadi — even if; mām — me; apratīkāram — without being resistant; aśastram — without being fully equipped; śastra-pāṇayaḥ — those with weapons in hand; dhārtarāṣṭrāḥ — the sons of Dhṛtarāṣṭra; raṇe — on the battlefield; hanyuḥ — may kill; tat — that; me — for me; kṣema-taram — better; bhavet — would be.

Translation:

Better for me if the sons of Dhṛtarāṣṭra, weapons in hand, were to kill me unarmed and unresisting on the battlefield.

Explanation:

Here in this verse, Arjuna now presents his conclusion:

yadi mām apratīkāram : “If I do not resist them,

aśastraṁ : not only am I not fighting them, but I don’t even have weapons with which to fight,

śastra-pāṇayaḥ : while my opponents have weapons in hand, raised and ready,

dhārtarāṣṭrā raṇe hanyus : if the sons of Dhṛtarāṣṭra, the Dhārtarāṣṭras, kill me in battle,

tan me kṣema-taraṁ bhavet : I feel that would be better.”

By using the word kṣema-taraṁ, Arjuna implies that this choice will lead to a better destination for him, offering greater protection.

Arjuna has previously spoken about how the world will become miserable if the entire dynasty, including its leaders and protectors, is destroyed. Not only will the current generation suffer, but previous generations will also fall from the higher realms, such as Pitṛloka. Both the destroyers and the destroyed, along with other dynasties, will endure suffering, and ultimately, the perpetrators of this destruction will face a prolonged stay in hell. Thus, there will be suffering on all fronts.

To avoid such a catastrophe, Arjuna is prepared to lose his own life. He understands that on the battlefield, the two main options are either to kill or be killed, and he is willing to die. Arjuna acknowledges that Duryodhana and his party are unlikely to have a change of heart, so even if he doesn’t fight, it won’t stop them from continuing the battle. Still, if they kill him, his suffering will end here. However, if he kills them, he will bear the responsibility for the destruction of the entire dynasty, leading to far greater suffering. Therefore, he concludes that it would be better for him to die weaponless and unresisting.

A kṣatriya is defined by the weapons he wields and the fighting spirit he embodies. For a kṣatriya to relinquish both—to become apratīkāram (unresisting) and aśastraṁ (without weapons)—is wholly uncharacteristic. Yet Arjuna is prepared to do just that, as his emotion-driven reasoning has clouded his judgment. Although he is, in one sense, making rational arguments, these arguments do not stem from a holistic understanding of reality. Instead, they arise from a fragmented perception in which Arjuna identifies himself and others primarily as bodies, thinking largely in terms of material well-being.

Arjuna uses the phrase “narake niyataṁ vāso” (Bhagavad-gītā 1.43), which indicates his belief in an afterlife. If life were merely a product of the body, there would be no one to go to naraka (hell). Although Arjuna acknowledges naraka, his conception remains largely material, leading him to focus on material well-being or suffering. Thus, he concludes that if fighting would lead to such misery, it would be better not to fight at all—even if it means setting aside his kṣatriya nature.

However, Kṛṣṇa will later emphasize that one’s nature cannot be changed—svabhāva-jena kaunteya nibaddhaḥ svena karmaṇā kartuṁ necchasi yan mohāt kariṣyasy avaśo ’pi tat (Bhagavad-gītā 18.60)—a point he reiterates at various other places in the Gītā as well. Here, however, Arjuna, based on his calculations of gain and loss, feels that dying on the battlefield is preferable to killing and facing the suffering of hell in the hereafter.

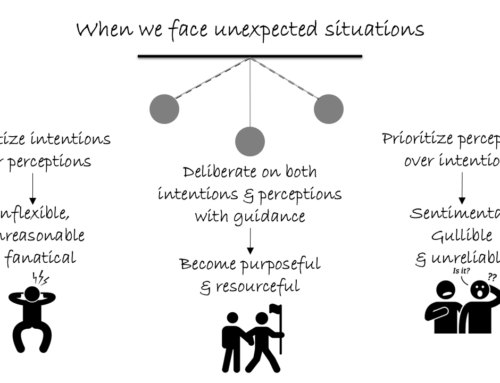

In spiritual cultures, it is understood that we must all account for our karma after death. That’s why the approach of death and awareness of mortality often make people more sober and serious about spiritual life. Arjuna’s stance here—refusing to fight—is, on one level, laudable, as he is willing to sacrifice his own life for the sake of peace and social order. However, on another level, his reasoning is also lamentable and incomplete, as he fails to fully consider the nature of the soul and its connection with God. It will take Kṛṣṇa’s instruction in the Bhagavad-gītā for Arjuna’s perception to become integrated rather than remain fragmented, allowing him to reach a proper understanding.

Arguments that arise from a fragmented perception, even if seemingly sound, are ultimately unsound. Arjuna’s reasoning is, in one sense, logical—Who will protect the dynasty? What will happen to the women and progeny if the dynasty falls? And what fate awaits someone who causes so much suffering in the world? These are all valid concerns.

However, the real issue is that Arjuna is considering valid points from a platform that is not ultimately valid. True welfare—whether for society or the individual—is not solely defined by bodily well-being. The soul, being eternal, requires consideration beyond material concerns. The Bhagavad-gītā even suggests that spiritual welfare may sometimes appear contrary to material welfare, though it ultimately is not. Establishing righteous rulers will, in fact, lead to material welfare as well. However, from a limited perspective, it may seem that prioritizing spiritual welfare contradicts immediate material concerns. At this point, Arjuna’s arguments reflect his incomplete perception—they do not reveal an understanding based on the level of the soul.

The point remains that Kṛṣṇa’s instructions, though they may initially appear disruptive—even disastrously so, as Arjuna predicts over here—are ultimately supremely redemptive. They restore order, bringing things to their ideal state. How this will unfold is not always clear to us, as we lack the omniscience of God.

Moreover, just as a patient may not fully understand why a doctor administers an injection or performs surgery, the doctor knows the purpose behind each action. Similarly, despite his knowledge, Arjuna is not a spiritual expert, which is why his reasoning falls short—even though his capacity for reasoning is strong.

Kṛṣṇa will guide Arjuna toward correct reasoning, and with this clarity, Arjuna will reach a conclusion that enlivens his resolve to fight the war.

Leave A Comment