Gita 01.39 Our Sense Of Honor Coming From Our Lineage Can Raise Us But Can Also Stop Us From Rising

kula-kṣaye praṇaśyanti

kula-dharmāḥ sanātanāḥ

dharme naṣṭe kulaṁ kṛtsnam

adharmo ’bhibhavaty uta

Word-for-word:

kula-kṣaye — in destroying the family; praṇaśyanti — become vanquished; kula-dharmāḥ — the family traditions; sanātanāḥ — eternal; dharme — religion; naṣṭe — being destroyed; kulam — family; kṛtsnam — whole; adharmaḥ — irreligion; abhibhavati — transforms; uta — it is said.

Translation:

With the destruction of the dynasty, the eternal family tradition is vanquished, and thus the rest of the family becomes involved in irreligion.

Explanation:

In this verse, Arjuna continues to express his reasons for not fighting. He speaks with great diligence, presenting various arguments for why he believes he should refrain from battle. In the previous verse, he mentioned that he could foresee the consequences of destroying the dynasty, and now he elaborates on those consequences.

kula-kṣaye praṇaśyanti: When the dynasty is destroyed,

kula-dharmāḥ sanātanāḥ: the eternal family traditions are lost.

dharme naṣṭe kulaṁ kṛtsnam adharmo ’bhibhavaty uta: and when the family traditions are lost, irreligion becomes prevalent.

Here, Arjuna uses the phrase ‘kula-dharmāḥ sanātanāḥ,’ which refers to kula-dharma as being sanātana (eternal). This juxtaposition of words is striking because kula-dharma is not typically considered sanātana. The true sanātana-dharma is the duty of the soul toward Kṛṣṇa. The soul’s eternal duty is to love Kṛṣṇa, and only this is truly sanātana—eternal. Everything apart from that is temporary.

We have various forms of dharma—whether we refer to it as duty, nature, responsibility, or role. In this world, there are many types of dharma, but the only sanātana dharma is the duty of the soul toward Kṛṣṇa. This eternal duty is not what Arjuna is referring to. In fact, in the first chapter of the Bhagavad-gītā, Arjuna does not mention this sanātana dharma at all. Instead, he places significant emphasis on kula-dharma—the duty to protect his lineage.

Arjuna then describes kula-dharma as sanātana, implying that it is eternal. The term ‘eternal’ can also be interpreted as meaning ancient or existing for a long time. On one level, we could say that these words are spoken by Arjuna under the influence of illusion, mistaking material aspects for the eternal. In reality, nothing material is eternal. This is akin to the portrayal in romantic movies and novels, where the concept of ‘happily ever after’ is prevalent. However, in the material world, there is no such thing as ‘happily ever after.’ Everything is temporary, and the nature of their happiness is also open to question. More importantly, nothing in the material world is truly eternal.

Furthermore, even our duties and associations with a dynasty are not eternal. We are souls on an eternal journey, and with each life, we are born into different dynasties, taking on different roles within them. Therefore, there is nothing in this world that warrants deep attachment. Yet, in this chapter, Arjuna appears to be enormously attached to the temporary, emphasizing his strong connection to familial duty.

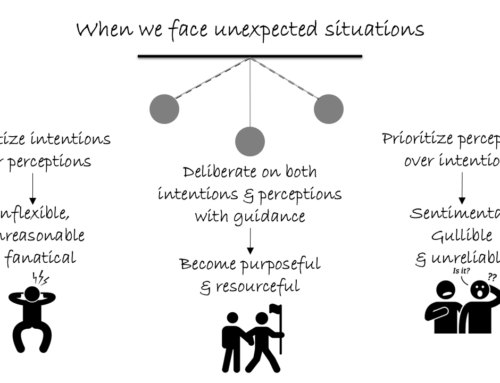

One aspect of attachment is that it distorts our perception, making less important things appear more significant and more important things seem less so. In the previous verse, Arjuna mentioned “lobhopahata-cetasaḥ,” referring to those who are blinded by greed and thus unable to see the harmful effects of fighting against family members. However, he believes that he can see these effects clearly.

The blinding nature of attachment is selective, not exhaustive. It is indeed exhausting, as we keep slaving for one object or another. In our pursuit of these objects, we inevitably experience suffering. The blinding effect of sense objects is something each of us must confront, shaped by our attachments. This blinding manifests not only in what we perceive—where some things are visible while others are not—but also in a warped sense of time. We start perceiving temporary things as eternal, while those that are truly eternal appear negligible or unworthy of consideration. This distortion keeps us bound to material existence, unable to properly process our desires and progress forward.

For each of us, it is essential to evaluate our conceptions in the light of reality, not in the distorted glow of sentimentality. We must examine them in the unsparing light of facts, not in the flickering light of emotions. While Arjuna’s feelings at this moment are not mundane or purely sensual, they remain nonspiritual and rooted in worldly concerns. He is contemplating the venerable tradition of the Kuru dynasty—a glorious lineage that has endured for generations. Arjuna worries about what will remain if the entire dynasty is destroyed. A sense of honor was always deeply ingrained in the warriors of that era, influencing their thoughts and actions significantly.

With that sense of honor, warriors were bound to confront whatever worldly situations they found themselves in, compelled to act according to what they believed was right. This deep-rooted sense of honor guided them and prevented them from engaging in dishonorable actions.

And yet, that very sense of honor can sometimes blind individuals to ultimate reality. The ultimate reality is that only the soul is eternal, and only the soul’s relationship with the Supreme Soul is everlasting. To the extent that this relationship is nurtured and focused upon, we grow in life. Conversely, when this relationship is neglected, we remain in ignorance, even if we appear materially highly knowledgeable. True knowledge is not just contextual; it is transcendental. While contextual knowledge is necessary, transcendental knowledge is equally essential.

Arjuna, driven by his deep veneration for tradition, fails to recognize that even these revered traditions are temporary. Everything material is fleeting, and clinging to them without understanding their impermanence can obscure one’s perception of ultimate reality.

What Arjuna considers to be sanātana-dharma is, in fact, not sanātana-dharma. He believes that his actions will preserve sanātana-dharma, but they may ultimately damage it. This is a key message that the Bhagavad-gītā will reveal. Mistaking the temporal for the eternal and the ephemeral for the everlasting is the essence of illusion. Whether it involves confusing something sensual with eternity or regarding a tradition as eternal, both are fundamentally temporal. Such misconceptions are inherently delusional.

The Bhagavad-gītā presents a sobering worldview, emphasizing that nothing in this material world will last forever. Therefore, we must direct our consciousness toward that which is eternal—the soul and its relationship with the Supreme Whole, as revealed throughout the text. Meanwhile, Arjuna is operating within a sattvic illusion, an illusion driven by the mode of goodness.

Leave A Comment