Gita 01.38 – Dont Let The Anartha – Maddened Make Us Similarly Mad

Audio Link 2: https://www.thespiritualscientist.com/gita-01-38-dont-let-the-anartha-maddened-make-us-similarly-mad/

kathaṁ na jñeyam asmābhiḥ

pāpād asmān nivartitum

kula-kṣaya-kṛtaṁ doṣaṁ

prapaśyadbhir janārdana

Word-for-word:

katham — why; na — should not; jñeyam — be known; asmābhiḥ — by us; pāpāt — from sins; asmāt — these; nivartitum — to cease; kula-kṣaya — in the destruction of a dynasty; kṛtam — done; doṣam — crime; prapaśyadbhiḥ — by those who can see; janārdana — O Kṛṣṇa.

Translation:

“O Janārdana, how can we, who clearly see the fault caused by the destruction of the dynasty, not refrain ourselves from committing this sin?”

Explanation:

Here, Arjuna continues to explain his reasoning for not wanting to fight in the impending Kurukṣetra war. He has earlier questioned, “What good can come from killing our relatives? Such actions will bring us immense sin.”

In response to the anticipated argument that if he refrains from killing, his enemies will kill him, Arjuna points out that the Kauravas are blinded by greed. However, he insists that he and the Pāṇḍavas do not need to act out of greed.

He elaborates further:

kathaṁ na jñeyam asmābhiḥ : “How can we, knowing this,

pāpād asmān nivartitum : not refrain from such sinful acts?

kula-kṣaya-kṛtaṁ doṣaṁ : The destruction of one’s dynasty is a grievous sin,

prapaśyadbhir janārdana : especially when we can see it so clearly, O Janārdana.

Arjuna appeals to Kṛṣṇa with these heartfelt words, emphasizing his awareness of the disastrous consequences of family destruction and his moral struggle in the face of this dilemma.

In the previous verse, Arjuna observed that the Kauravas are blinded by greed, which prevents them from recognizing the grievous sin they are about to commit. He contrasts their mindset with his own, stating that he and the Pāṇḍavas are not similarly blinded—they can see the consequences clearly.

Arjuna, taking the higher moral ground, questions how they can lower themselves to the same debased level as the Kauravas. He argues that they should not stoop to responding to evil with evil. This reasoning reflects a valid moral principle—one should not let another’s wrongdoing dictate one’s own actions.

However, what Arjuna fails to recognize—and what Kṛṣṇa will instruct him through the Bhagavad-gītā—is that Kṛṣṇa’s response is not about responding to evil with evil. Instead, Kṛṣṇa is guiding them to respond to evil by establishing dharma. Whatever it takes to uphold and re-establish dharma, they must be prepared to do.

Arjuna is concerned that by fighting for the kingdom, they will be acting out of the same greed as the Kauravas, driven by the desire to possess land. He fears that such actions will blind them to higher values, just as greed has blinded the Kauravas.

However, Kṛṣṇa assures Arjuna that this is not the case. He explains that they will not be acting on the materialistic plane of greed but on a higher level of consciousness. Kṛṣṇa emphasizes that their actions are for Him, guided by the understanding that they are eternal souls. The dharma of the soul is to serve Kṛṣṇa, and when the soul inhabits the body of a kṣatriya, its dharma is to act on Kṛṣṇa’s behalf to establish righteousness in the world.

Kṛṣṇa clarifies that they are not fighting merely to reclaim the kingdom for personal gain, as Arjuna himself lacks such greed. Instead, their fight is to re-establish dharma, ensuring that the citizens are governed by a righteous king and are supported in following the path of dharma.

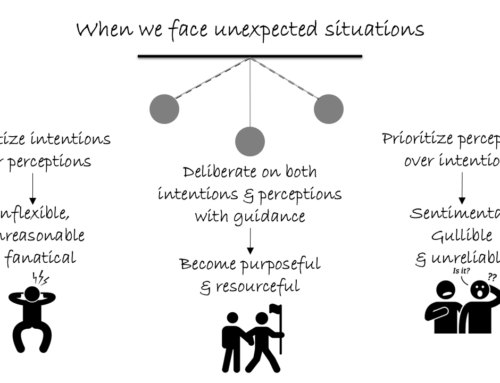

All of this will be revealed to Arjuna later, and understanding this higher revelation will completely transform his perspective. However, at his current level, Arjuna is presenting a reasonable argument—just because others are blinded by greed does not mean we should become greedy. Similarly, just because others succumb to anger does not mean we should allow anger to control us.

That said, Arjuna’s argument does not advocate passivity. Not becoming angry does not mean passively accepting injustice, allowing others to trample on us, exploit us, or destroy us. Instead, it means responding to anger and injustice appropriately. The key is to act in a way that rectifies the situation and sets it right, guided by dharma and the greater good.

In this world, people often act sinfully, viciously, or maliciously. During such times, we may feel a strong impulse to retaliate in kind, responding to harm with harm. In certain situations, particularly for kṣatriyas, taking assertive action may indeed be necessary. However, this does not mean we should lower our consciousness to the same level as those acting out of malice.

We can always remember our spiritual identity, purpose, and connection with Kṛṣṇa, allowing us to act in alignment with spiritual truth. The phrase ‘prapaśyadbhir’ emphasizes this point—encouraging us to see with the eyes of knowledge and act accordingly.

In general, anarthas blind us to everything except the objects that attract and entangle us. This fixation caused by anarthas leaves us with nothing but misery, as they obscure our higher purpose and true happiness. When trapped in this state of suffering, the natural response is to cry out for succor, to beg for help. However, relief does not come unless we strive to rise to a higher level of consciousness, transcending the hold of these anarthas and reconnecting with our spiritual essence.

Otherwise, anarthas keep us trapped in a cycle of suffering and illusion. The way out of this entrapment is to connect with Kṛṣṇa, purify ourselves, and elevate our consciousness.

For example, hatred cannot be ended by more hatred. As the Bible teaches, “Hate not the sinner, hate the sin.” This principle does not imply that sinners should escape accountability. Rather, it means the sinner should not become the object of hate. Whatever is necessary for their correction should be done—whether that involves punishment or, if the sinner is genuinely repentant, forgiveness. The response should be guided by dharma and aimed at rectification, not vengeance.

The crucial point is that we should not allow others’ misbehavior to provoke similar misbehavior within us. Instead, we must act according to our principles, remembering ‘prapaśyadbhir’—to see reality clearly and act in alignment with that vision.

For instance, if we enter a mental asylum and a person there begins screaming, yelling, and shouting profanities at us, the words they use may be very cruel and hurtful. In such a situation, we might feel a strong impulse to retaliate and start hurling profanities in return.

If we pause, check our impulses, and reflect, we will realize that the person is in a disturbed state, not fully in control of their actions. Responding in the same manner—matching their anger and cruelty—will not help them or the situation. We must ask ourselves, “Is it really worthwhile for me to take their words seriously?” In the same way, anarthas madden people in this world, causing them to act in irrational or harmful ways, including hurting others.

Indeed, if the madman is attacking a visitor in the asylum, the situation must be addressed. The madman may need to be restrained, regulated, or even disciplined, and in some cases, punishment may be necessary. However, the key point is that the guards or caregivers of the madman are not meant to descend to the madman’s level and react in the same way. Instead, their role is to protect themselves, protect the madman, and act in a manner that supports the madman’s recovery. They should respond with the intention of helping, maintaining their composure, while ensuring the safety and well-being of all involved.

Similarly, when people in this world are blinded by anarthas and act in harmful or irrational ways, it does not mean that we should become blinded ourselves and act in the same way. Instead, we must maintain our clarity of vision and our discernment, responding appropriately to the situation. Our focus should be on doing whatever it takes to stay on the path of dharma, spiritual illumination, and devotional liberation. At the same time, we should seek to help others, even those who are blinded by lust or other anarthas, guiding them as much as possible on the same path toward spiritual growth and liberation.

For Arjuna, the path of dharma meant fighting against Duryodhana and the Kauravas, as they had shown themselves to be incorrigible in their actions. Arjuna’s fight would not be for personal gain or to merely grab the kingdom, as the Kauravas sought. Rather, his battle was by the will of the Lord, to assist in the re-establishment of dharma. As the Bhagavad-gītā unfolds, this higher purpose will be revealed to Arjuna, clarifying that his role in the battle is part of a divine plan to restore righteousness and guide the world back to its rightful order.

Leave A Comment