Gita 01.35 – Arjuna’s Profit – Loss Calculations Miss The Most Important Factor

Audio Link 2: https://www.thespiritualscientist.com/gita-01-35-arjunas-profit-loss-calculations-miss-the-most-important-factor/

api trailokya-rājyasya

hetoḥ kiṁ nu mahī-kṛte

nihatya dhārtarāṣṭrān naḥ

kā prītiḥ syāj janārdana

Word-for-word:

api — even if; trai-lokya — of the three worlds; rājyasya — for the kingdom; hetoḥ — in exchange; kim nu — what to speak of; mahī-kṛte — for the sake of the earth; nihatya — by killing; dhārtarāṣṭrān — the sons of Dhṛtarāṣṭra; naḥ — our; kā — what; prītiḥ — pleasure; syāt — will there be; janārdana — O maintainer of all living entities.

Translation:

O maintainer of all living entities, I am not prepared to fight with them even in exchange for the three worlds, let alone this earth. What pleasure will we derive from killing the sons of Dhṛtarāṣṭra?

Explanation:

In this verse, Arjuna continues explaining why he refuses to fight:

api trailokya-rājyasya: “Even if I were to gain sovereignty over the three worlds,

hetoḥ kiṁ nu mahī-kṛte: what to speak of merely ruling this earth?

nihatya dhārtarāṣṭrān naḥ: If we have to kill the sons of Dhṛtarāṣṭra,

kā prītiḥ: what pleasure would we gain from it?

syāj janārdana: O Kṛṣṇa, O Janārdana, protector of the people, why do you urge me to kill the sons of Dhṛtarāṣṭra?”

Arjuna expresses his reluctance to engage in battle, questioning the value of even the highest rewards if they come at the cost of killing his kin. His heart cannot find joy in such an outcome, and he appeals to Kṛṣṇa, highlighting his inner conflict.

The question here primarily concerns priority. Arjuna is strongly expressing his opposition to killing the Kauravas. He suggests that if one thinks in terms of profit-and-loss calculations—such as gaining a kingdom—sometimes hard decisions must be made. For instance, a student who aspires to a bright future may have to leave behind loving family members to attend a distant college. Similarly, an athlete aiming to excel in a particular sport might need to forgo favourite foods to maintain the required level of fitness.

Achieving anything significant in life often requires tough decisions, which we frequently base on profit-and-loss calculations. If the potential gain outweighs the loss, we generally proceed with the decision. In such a trade-off, however, what is considered valuable is subjective and varies from person to person. For example, some might feel that a high-paying job with excellent career prospects is not worth prolonged separation from family. Others may think, “I can be away—after all, I’m working and earning for my family—I’ll send them the money.”

In real-life profit-and-loss calculations, an element of subjectivity is inevitable. Different people value different things according to their individual nature and mentality, leading to diverse priorities and choices.

Here, Arjuna offers his personal evaluation, responding to any argument that gaining a kingdom would justify fighting and killing relatives. He conveys, “I don’t consider it worth it at all. Not only the kingdom—even if someone offered me sovereignty over the three worlds, I would not accept it. To me, not even all three worlds are worth killing my relatives.” Through this statement, Arjuna emphasizes the depth of his reluctance, illustrating that no worldly reward could justify such a severe act in his eyes.

It is noteworthy that Arjuna uses the term ‘dhārtarāṣṭrān naḥ.’ Here, he isn’t merely referring to Bhīṣma and Droṇa, to whom he has a natural affection as venerable elders—he is also including the Kauravas. His stance is not driven solely by considerations of affection. This becomes clear in the next verse, where he speaks about the sinful reactions associated with killing one’s relatives—a serious concern weighing heavily on him, which we will discuss further.

Arjuna’s intent is to categorically dismiss any argument based on profit-and-loss calculations. He is stating that such calculations hold no value for him—for him, the act of killing relatives far outweighs the prospect of gaining any kingdom, even sovereignty over the three worlds, let alone an earthly kingdom.

At one level, Arjuna is indeed valuing people over possessions, and this is admirable if the situation was that straightforward. However, Kṛṣṇa will soon reveal that the battle is not merely about claiming a kingdom—it serves a much higher purpose. As the narrative of the Bhagavad-gītā progresses, this purpose unfolds, emphasizing spiritual welfare for everyone involved by aligning with Kṛṣṇa’s will.

In terms of profit-and-loss calculations, fulfilling his duty in service to Kṛṣṇa yields the greatest benefit—not just for Arjuna, but for others as well. Without Kṛṣṇa’s guidance, those on the opposing side would continue to perform bad karma, act against divine will, and ultimately suffer the consequences in the long run. Arjuna, however, has yet to consider this factor. Thus, despite his emotionally riveting and seemingly well-reasoned argument, his argument remains flawed due to this incomplete perspective.

It is said in the Mahābhārata and also by Cāṇakya that for the sake of a family, one family member may be sacrificed; for the sake of a village, a family may be sacrificed; for the sake of a kingdom, a village may be sacrificed. But for the sake of the soul, the entire world may be sacrificed. This hierarchy places our spiritual welfare above all else. Similarly, in the biblical tradition, it is asked, “What profiteth a person if he gains the whole world but loses his eternal soul?”—for even the entire world is temporary. Only by attaining eternal life do we achieve something lasting forever. To gain this eternal life is to realize our spiritual identity and rise to the spiritual plane, which alone is everlasting.

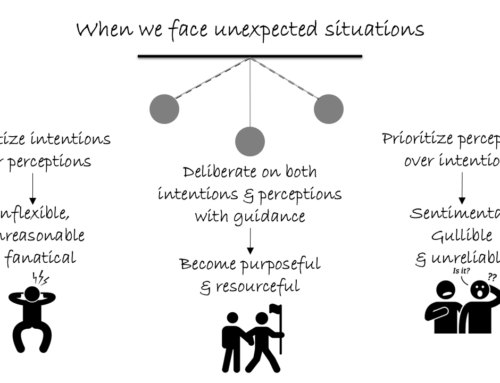

Arjuna is presenting his reasoning, and Kṛṣṇa will use this same line of thought to expose the flaws in Arjuna’s perspective by highlighting the crucial factors he has overlooked. In spiritual practice, we are guided by the principle of accepting what is favorable and rejecting what is unfavorable—these are the first two aspects of surrender. This means that we should consider our circumstances and discern what actions align with our spiritual goals. We can indeed engage in profit-loss considerations, but not for our personal gain. Rather, we assess them in terms of how they benefit our service to Kṛṣṇa and deepen our relationship with Him. Our decisions are guided by what brings us closer to Kṛṣṇa and what distances us from Him, and we choose our actions accordingly.

The issue is not simply choosing between kin and kingdom—kin represents relationships, while a kingdom signifies possessions. Rather than framing the choice as Arjuna does, it is fundamentally about moving closer to Kṛṣṇa or moving away from Him. In Arjuna’s particular situation, the wisdom of the Gītā will reveal that fighting is the path that aligns best with his duty and his spiritual welfare. How this unfolds and why it is the best course for him will be discussed as the teachings progress.

Leave A Comment