Gita 01.35 Our Pleasure – Pain Calculation Determines Our Decisions And Is Determined By Our Worldview

Audio Link 1: Gita 01.35 Our pleasure-pain calculation determines our decisions and is determined by our worldview

api trailokya-rājyasya

hetoḥ kiṁ nu mahī-kṛte

nihatya dhārtarāṣṭrān naḥ

kā prītiḥ syāj janārdana

Word-for-word:

api — even if; trai-lokya — of the three worlds; rājyasya — for the kingdom; hetoḥ — in exchange; kim nu — what to speak of; mahī-kṛte — for the sake of the earth; nihatya — by killing; dhārtarāṣṭrān — the sons of Dhṛtarāṣṭra; naḥ — our; kā — what; prītiḥ — pleasure; syāt — will there be; janārdana — O maintainer of all living entities.

Translation:

O maintainer of all living entities, I am not prepared to fight with them even in exchange for the three worlds, let alone this earth. What pleasure will we derive from killing the sons of Dhṛtarāṣṭra?

Explanation:

In this verse, Arjuna continues his argument, refusing to fight against the Kauravas. He says:

api trailokya-rājyasya: Even for gaining a kingdom of the three worlds,

hetoḥ kiṁ nu mahī-kṛte: it’s not worth it to fight against them.

nihatya dhārtarāṣṭrān naḥ: If we kill the sons of Dhṛtarāṣṭra,

kā prītiḥ syāj janārdana: what pleasure will we get, O Janārdana? What is there to gain in it?

Essentially, Arjuna is saying that if he wouldn’t fight even for the rule of the three worlds, then why would he do it merely to gain the earth? What pleasure is there in that?

All of us function based on a pleasure-pain calculation. We seek pleasure and aim to avoid pain. In every situation, we assess what will bring us pleasure and pursue those things while trying to avoid what may cause us pain.

If some things bring us more pleasure than pain, we generally consider them worth pursuing. Rarely, however, are situations purely black and white—very few things bring only pleasure or only pain. When faced with choices that involve both, we make comparisons: What brings more pleasure or what causes more pain? We then decide accordingly—engaging in the activity if the pleasure outweighs the pain or avoiding it if the pain is greater.

Yet, the pleasure-pain calculations we make are often far from objective. They can’t be entirely objective, as our emotional responses to life’s upheavals cannot be precisely quantified.

For example, for someone who loves cricket, paying a lot of money to watch a match at a famous ground feels worthwhile—even braving the crowds adds to the enjoyment. However, someone who isn’t a cricket fan would see it as a waste of time, money, and convenience.

When we are asked to do something specific, like working overtime, our pleasure-pain assessment will depend on our current priorities. If we are in urgent need of money or aiming for a raise or promotion, we may feel that working overtime is worthwhile. However, if we value spending time with family or dedicating time to spirituality, we might feel that, despite the extra money, working overtime isn’t worth it. Not only do different people assess pleasure and pain differently, but the same person may also evaluate it differently at various stages of life.

Therefore, we have a reference point and a background context based on which we analyze pleasure and pain. Understanding this context is essential for making objective evaluations. Arjuna is engaged in a pleasure-pain calculation and concludes that fighting is simply futile. He reflects on what he will gain by fighting. Ultimately, he sees that all he would gain is a kingdom, but any pleasure from that kingdom is far outweighed by the pain he will experience from the loss of his family members. The pain will not come from some force of nature; rather, he will be the cause of their deaths, and that burden will be unbearable.

He is employing this pleasure-pain calculation and concludes that he certainly cannot fight against the Kauravas, the ‘dhārtarāṣṭrā’. Interestingly, Arjuna does not refer directly to Duryodhana; instead, he uses the term ‘dhārtarāṣṭrān’ because it encompasses all the hundred Kauravas he must face, not just Duryodhana. This choice reflects his recognition of their relationship with their elder. Although Dhṛtarāṣṭra never truly acted as an affectionate father figure, the Pāṇḍavas still held some respect for him as their uncle.

Hence, ‘dhārtarāṣṭrān naḥ’ serves as an inclusive term for the sons of Dhṛtarāṣṭra. Arjuna recognizes that by killing them, any gain he might achieve will not be enough to outweigh the pain of not only losing them but also being the cause of their deaths. While he is conducting a pleasure-pain calculation, the Bhagavad-gītā will provide him with a deeper reference point and a broader framework for this analysis, leading to a reversal of his decision.

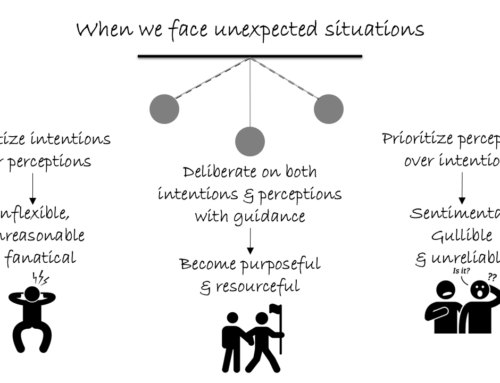

However, the principle that our pleasure-pain analysis is foundational to our decision-making influences our worldview, priorities, purposes, and principles. These elements come together to tilt the scales in a particular direction in our pleasure-pain evaluation, depending on who we are or who we perceive ourselves to be. Our understanding of what is most important in our lives—our interests, purposes, and values—shapes how we perceive certain things as highly pleasurable or highly painful.

Our pleasure-pain analysis fundamentally determines our decision-making, while our worldview shapes that analysis. To the extent we align our worldview with reality, our pleasure-pain analysis will become more objective, resulting in better decisions. The Bhagavad-gītā will assist Arjuna in making a sound decision by introducing objectivity, harmonizing his worldview with reality, thereby enhancing the objectivity of his pleasure-pain analysis. This process will bring clarity and maturity to his decision-making.

Leave A Comment