Gita 01.34 – Arjuna’s Evolved Emotion And Reason Ready To Be Raised To The Summit By Gita Wisdom

mātulāḥ śvaśurāḥ pautrāḥ

śyālāḥ sambandhinas tathā

etān na hantum icchāmi

ghnato ’pi madhusūdana

Word-for-word:

mātulāḥ — maternal uncles; śvaśurāḥ — fathers-in-law; pautrāḥ — grandsons; śyālāḥ — brothers-in-law; sambandhinaḥ — relatives; tathā — as well as; etān — all these; na — never; hantum — to kill; icchāmi — do I wish; ghnataḥ — being killed; api — even; madhusūdana — O killer of the demon Madhu (Kṛṣṇa)

Translation:

Maternal uncles, fathers-in-law, grandsons, brothers-in-law, and other relatives — I do not wish to kill them, even if they attack me, O Madhusūdana.

Explanation:

Arjuna continues listing those who would be killed if he persists in this war. The Bhagavad-gītā presents a similar list for the second time—the first instance appears in verse 1.26, where Arjuna sees his relatives amidst both armies (tatrāpaśyat sthitān pārthaḥ pitṝn atha pitāmahān).

In the first case, it is Sañjaya, the narrator, who describes this list. Here, however, Arjuna himself provides the description. In both instances, the emphasis is on the many relatives gathered on the battlefield, whose deaths would result in emotional and social devastation.

The social disaster will be elaborated upon later, in verses 39, 40, and 41 onward. At this point, however, Arjuna is focused on the emptiness of life without his loved ones and identifies who those loved ones are—those without whom he would have to continue living. This is his focus here.

There is a subtle difference between the two lists. In the first list, Pārtha (Arjuna) sees his relatives, while Sañjaya describes them. A similar structure appears in Chapter 11 with the threefold description of the Viśvarūpa (universal form). First, Kṛṣṇa describes what he is about to reveal, followed by Sañjaya’s account of what Arjuna is witnessing, and finally, Arjuna’s own description of what he sees.

In Chapter 11, Arjuna’s description is the longest, though it is preceded by two accounts. Here, in contrast, we have a double description—first, Sañjaya describes what Arjuna sees, and then Arjuna recounts his experience.

When Sañjaya describes the scene, the verse reads:

tatrāpaśyat sthitān pārthaḥ

pitṝn atha pitāmahān

ācāryān mātulān bhrātṝn

putrān pautrān sakhīṁs tathā

śvaśurān suhṛdaś caiva (Bg 1.26)

This translates as “fathers, grandfathers, teachers, maternal uncles, brothers, sons, grandsons, friends, fathers-in-law and intimate friends.” Here, sakhīṁs refers to general friends, while suhṛdaś signifies friends with whom one shares a deep, heart-to-heart connection. Here, Sañjaya essentially describes ten different categories of people.

Śrīla Prabhupāda combines verses 1.32-35 since it represents a single unit of thought, and the list presented in 1.33-34 is as follows:

ācāryāḥ pitaraḥ putrās tathaiva ca pitāmahāḥ — teacher, father, son, grandfather

mātulāḥ śvaśurāḥ pautrāḥ — maternal uncle, father-in-law, grandson.

Up to this point, the list aligns with the previous one. However, here Arjuna adds śyālāḥ sambandhinas tathā — brothers-in-law and other relatives. This list omits bhrātṝn (brothers), sakhīṁs (general friends), and suhṛdaś (heart-to-heart friends), placing a greater emphasis on Arjuna’s familial relations.

Arjuna questions how he can find happiness by killing his own people. In this context, he lists various relatives, including śyālāḥ (brothers-in-law) and sambandhinas tathā, a general describer for all relatives.

The term ‘brothers-in-law’ can refer to multiple individuals, potentially even Jayadratha in an extended sense. Jayadratha was married to Lakṣmaṇā, who was like a sister to the Pāṇḍavas, including Arjuna, although she was actually Duryodhana’s sister.

Arjuna states, etan na hantum icchāmi—”I cannot bring myself to kill them, even if they decide to kill me.” He follows with ghnato ’pi madhusūdana, highlighting that in war, either one wins, or the opponent does, implying that losing means his own death. Still, he says, “Even if they kill me, I cannot bring myself to kill them.” He questions, “What good is there in that? What happiness will come from such an act?” This reveals the depth of Arjuna’s concern and the strength of his inner principles—he is even willing to even court death rather than betray his conscience.

These principles may not represent the highest ideals, and Kṛṣṇa will soon reveal the ultimate principle—acting for one’s own spiritual welfare and that of others through devotional service to Him. Yet, even at this level, Arjuna’s struggle is not merely a case of nerves or a last-minute breakdown but a profound moral dilemma rooted in his values.

Sometimes, cricketers choke at critical moments. The tension overwhelms them, and although they know the right approach—remain calm, focus, and play on—they simply cannot perform.

However, Arjuna’s situation is not a case of choking. He is not merely faltering under pressure—he is presenting reasons for his reluctance. While his reasoning may not align with the ultimate spiritual perspective, it is thoughtful at his level. Arjuna reflects on the futility of killing his own kin, and he evaluates the consequences, noting, “If I don’t kill, they may kill me.” Yet, he is willing to accept that outcome, preferring it over the alternative of killing his own people. The extent of his resolve will become even more apparent in the verses that follow.

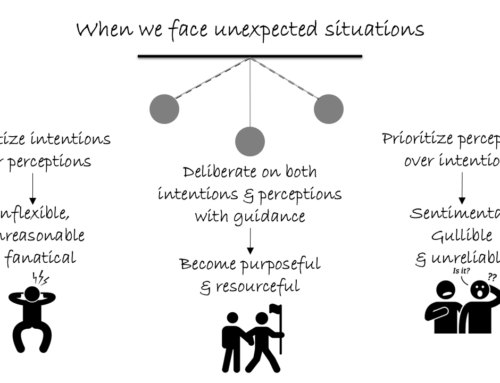

Here, we observe both Arjuna’s affection for his relatives and his capacity for reason. Both his emotional depth and his logical reasoning will be elevated by the wisdom of the Gītā. Arjuna will eventually reverse his decision and choose to fight—not because he becomes indifferent or heartless, but because the wisdom of the Gītā will expand his understanding. It will help him recognize that fighting is ultimately beneficial, both for himself and for others involved. This shift in perspective will only be possible once he attains spiritual vision. At this moment, however, his material vision leads him to believe that fighting is futile—he is even willing to accept his own death to avoid what he sees as meaningless conflict. Through his words, Arjuna reveals his sensitivity and thoughtfulness.

Leave A Comment