Gita 01.12: Just because we get others to do what we want them to do doesn’t mean we have won them over to our side

Audio Link 1: Gita 01.12 just get others want doesn’t mean won side

tasya sañjanayan harṣaṁ

kuru-vṛddhaḥ pitāmahaḥ

siṁha-nādaṁ vinadyoccaiḥ

śaṅkhaṁ dadhmau pratāpavān

Word-for-Word:

tasya — his; sañjanayan — increasing; harṣam — cheerfulness; kuru-vṛddhaḥ — the grandsire of the Kuru dynasty (Bhīṣma); pitāmahaḥ — the grandfather; siṁha-nādam — roaring sound, like that of a lion; vinadya — vibrating; uccaiḥ — very loudly; śaṅkham — conchshell; dadhmau — blew; pratāpa-vān — the valiant.

Translation:

Then Bhīṣma, the great valiant grandsire of the Kuru dynasty, the grandfather of the fighters, blew his conchshell very loudly, making a sound like the roar of a lion, giving Duryodhana joy.

Explanation:

This verse represents a shift from discussion to action in the Bhagavad Gita’s first chapter. A few verses later, there will again be a transition from action to discussion. The verse begins with “tasya,” referring to Duryodhana, who has been the focus of the vision of the Gita. As far as the battlefield setting is concerned, the Gita begins with Duryodhana’s actions on the battlefield.

“Tasya sañjanayan harṣaṁ” translates to increasing his jubilation; “kuru-vṛddhaḥ pitāmahaḥ” identifies Bhīṣma as the elderly grandsire of the Kuru dynasty; “siṁha-nādaṁ vinadyoccaiḥ” means he spoke in a voice as powerful as a lion’s roar; and “śaṅkhaṁ dadhmau pratāpavān” signifies that he blew his conch shell, a traditional call to battle. The term “pratāpavān” describes Bhīṣma as heroic, highlighting his valor and reputation.

Bhīṣma is described with multiple epithets that emphasize his stature and capabilities: “kuru-vṛddhaḥ” indicating he is the elderly grandsire. The term “vrddhah,” typically means old, but in this context, it also conveys wisdom, experience, and seasoned, just as “samvrddhah” conveys a prosperous and a flourishing state of being. The phrase “siṁha-nādaṁ vinadyoccaiḥ” describes the act of Bhīṣma blowing his conch shell with a thunderous roar, akin to a lion.

Also, the word “pratapavan” (saṅkhaṁ dadhmau pratāpavān) signifies that Bhīṣma is an extraordinary personality with a history of heroic deeds. He has fought many wars and defeated some of the greatest warriors single-handedly. His presence is crucial for Duryodhana. If Duryodhana has any apprehensions about Bhīṣma’s readiness to fight, they are allayed by Bhīṣma’s fierce blowing of the conch shell.

On the battlefield, the blowing of the conch shell is a statement of intent, signalling the actions that are about to be taken. If there is a fight between two boxers or two fighters and one of them speaks very meekly, it might suggest that this person lacks fighting spirit. However, if both fighters are roaring vigorously, it indicates that both are determined to fight.

Similarly, Bhīṣma blew his conch shell so loudly that it sounded like a lion’s roar. On hearing that, Duryodhana’s jubilation increased, which is what he was seeking. Duryodhana had become somewhat rattled by seeing the strength and expertise of the Pāṇḍava army. He had expected this to be an easy victory, but the Pāṇḍavas were far better prepared and more determined than he had anticipated. He had thought, “My forces are much greater than theirs; they will cower in fear at the thought of fighting against me.” Of course, this was unrealistic, considering the Pāṇḍavas themselves were great heroes. However, Duryodhana’s pride in his political abilities, which had allowed him to form numerous alliances and gather many warriors, led him to be shocked and taken aback by the fierce fighting spirit of the opposing side. His purpose was to invoke a similar fierce fighting spirit among his own warriors. The two warriors he relied on most, but who had weaker emotional connections and commitment to him, were Bhīṣma and Droṇa. He first spoke to Droṇa and then indirectly to Bhīṣma, within Bhīṣma’s earshot. When Bhīṣma blew the conch shell, Duryodhana felt that his speech had been successful.

If a child has been cranky and is not studying or following their parents’ instructions, and the parents manage to persuade the child, the parents feel happy. They feel that their efforts were successful, as it can be challenging to manage such situations. When we speak and our words achieve their intended purpose, it brings us joy. On the battlefield, Duryodhana had a specific goal: to motivate Droṇa and Bhīṣma to fight wholeheartedly. Duryodhana wanted to ensure that the elders were fully committed to fighting for him. When he felt that he had accomplished this, he felt jubilant (tasya sañjanayan harṣaṁ).

From Bhīṣma’s perspective, was it Duryodhana’s diplomatic juggling of various interests that had worked or was it something else? In reality, it was much more than that. Bhīṣma was not eager for war, but he knew it was inevitable and had grown weary of Duryodhana’s machinations. He felt that it was time to begin the battle, thinking, “That’s enough; now let’s start fighting.” Whether or not Duryodhana had completed his speech, which was generally addressed to everyone, Bhīṣma felt it was time to commence hostilities. There is no indication in the Gita that Duryodhana signaled to Bhīṣma to take over after his speech. Nonetheless, Bhīṣma blew the conch, marking the start of the conflict.

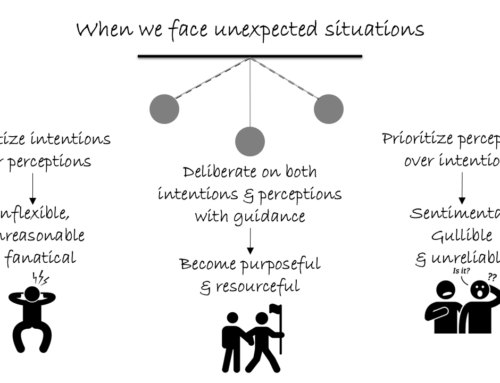

When we speak to get others to do something, we often don’t know if they are doing it for the reasons we intended or for their own reasons. We have our own intention behind an action and want others to join us in it, but their motivations may differ from ours. Duryodhana’s main concern was that Droṇa and Bhīṣma might not fight wholeheartedly. While Bhīṣma did fight wholeheartedly, his motivation was for a transcendental purpose.

On the ninth day, Bhīṣma fought with such vehemence, especially against Arjuna, that Kṛṣṇa was forced to pick up a weapon to defend His dear devotee. In doing so, Bhīṣma demonstrated to the world Kṛṣṇa’s great devotion to His devotees and how unfailingly He protects them. When we congratulate ourselves for getting someone to do something, we should avoid being premature in our praise. We might not have won others to our way of thinking, but they may have circumstantially agreed to our plans due to entirely different motives. Such are the subtleties of the human mind, and while the Bhagavad Gita will later provide deeper insights into how the mind operates, it begins to reveal this complexity in its first chapter.

Thank you.

Leave A Comment