Gita 01.42 – Three Meanings Of Dharma

Audio Link 2: https://www.thespiritualscientist.com/gita-01-42-three-meanings-of-dharma/

doṣair etaiḥ kula-ghnānāṁ

varṇa-saṅkara-kārakaiḥ

utsādyante jāti-dharmāḥ

kula-dharmāś ca śāśvatāḥ

Word-for-word:

doṣaiḥ — by such faults; etaiḥ — all these; kula-ghnānām — of the destroyers of the family; varṇa-saṅkara — of unwanted children; kārakaiḥ — which are causes; utsādyante — are devastated; jāti-dharmāḥ — community projects; kula-dharmāḥ — family traditions; ca — also; śāśvatāḥ — eternal.

Translation:

By the evil deeds of those who destroy the family tradition and thus give rise to unwanted children, all kinds of community projects and family welfare activities are devastated.

Explanation:

doṣair etaiḥ kula-ghnānāṁ: Due to the fault of those who destroy the kula (family or lineage)

varṇa-saṅkara-kārakaiḥ: and the resulting creation of varṇa-saṅkara (unwanted progeny),

utsādyante jāti-dharmāḥ: there will be a devastation of jāti-dharma—the duties and responsibilities of each community, or “community projects” as Śrīla Prabhupāda translates

kula-dharmāś ca śāśvatāḥ: and, as Śrīla Prabhupāda translates, of eternal family traditions (kula-dharma).

In this verse, Arjuna discusses how dharma will be devastated if they proceed with the war, leading to the destruction of the dynasty. The underlying message of his statement is that they should avoid fighting to prevent this disruption.

This raises an important question: Arjuna speaks of dharma being destroyed, yet we often hear Śrīla Prabhupāda explaining that dharma is the essential, inalienable characteristic of the soul. So how can something that is the soul’s essential, inalienable characteristic be destroyed?

The word ‘dharma’ indeed has many meanings, and one foundational aspect, often overlooked, is its connection to our core nature—the inclination to love and serve. When this intrinsic nature of loving and serving is directed toward the eternal—toward Kṛṣṇa—it brings us lasting happiness. At the level of the soul, this loving service is our true nature and, in fact, our dharma—to love and serve constantly and eternally.

Along with that, the word dharma has other meanings as well. For example, in Bhagavad-gītā 4.8, when Kṛṣṇa states, “dharma-saṁsthāpanārthāya sambhavāmi yuge yuge”—that He descends to establish dharma—it raises an important question. If dharma is simply an essential, inalienable nature, then why does Kṛṣṇa need to descend to establish it? Kṛṣṇa speaks of actually destroying miscreants and proclaiming dharma as authoritative. Is He referring only to the individual heart, or is He also speaking at the societal level?

Surely, Kṛṣṇa is asking Arjuna to fight a war. So, there is definitely a social dimension to the project of establishing dharma. In establishing dharma at the social level by installing Yudhiṣṭhira (Dharmarāja) as king, how does this relate to the idea of dharma as the soul’s innate nature?

Firstly, if something is innate, why does it need to be established? Why must it be established externally in society?

Secondly, towards the end of the Gītā, in 18.66, Kṛṣṇa says, “sarva-dharmān parityajya mām ekaṁ śaraṇaṁ vraja; ahaṁ tvāṁ sarva-pāpebhyo mokṣayiṣyāmi mā śucaḥ”—”Abandon all varieties of dharma and surrender to Me alone. I shall deliver you from all sinful reactions. Do not fear.” Here, He says to give up all varieties of dharma. If dharma is an essential, inalienable nature, then why would we need to give it up?

To understand such seemingly contradictory statements, we need to explore the various meanings of the word dharma. One meaning refers to the spiritual level—the natural, spontaneous attraction of the soul to serve Kṛṣṇa. This is not simply a choice at the pure spiritual level—it is the very nature of the soul. This is sanātana-dharma, the eternal duty to love and serve Kṛṣṇa. It is also called siddha-dharma, meaning the state of those who are perfected (siddhas) and are spontaneously absorbed in love for Kṛṣṇa.

However, right now we are sādhakas (practitioners); so, we need a process to rise from the sādhaka stage to the siddha stage. Just as one needs a pathway to travel from Pune or Mumbai to Vṛndāvana or Māyāpura, we also need a pathway to elevate our consciousness to the spiritual level. This pathway is the sādhaka’s dharma. Hearing, chanting, and engaging in service are part of this sādhaka’s dharma, and by following it, we gradually rise from material consciousness to spiritual consciousness. At the spiritual level, we begin to realize and relish our innate dharma of loving and serving Kṛṣṇa.

When we live in this world, we are spiritually impoverished and therefore need to practice sādhanā-bhakti as a form of treatment. However, along with that, we also have to live in this world, within a particular society, dynasty, or profession. In each of these contexts, we have duties according to our material situations. These duties, in and of themselves, may not be spiritual, but they are not unimportant. They are important because they enable society to function properly and allow us to function responsibly as members of society. Thus, such dharmas can be various, and here Arjuna is referring to two of them—jāti-dharma and kula-dharma.

What does jāti refer to? Usually, we focus on varṇāśrama, which is based on guṇa (qualities) and karma (capacities for work). This is definitely true, but from a functional sociological point of view, jāti also plays a significant role in India. Jāti is actually a subdivision within varna. Thus, there can be different groups within the brāhmaṇa, kṣatriya, vaiśya, and śūdra categories.

For example, when Śrī Caitanya Mahāprabhu went to Vṛndāvana, the Sanodiyā brāhmaṇa was hesitant to invite Him to take food at his house. Although he was a brāhmaṇa and Caitanya Mahāprabhu would only take food at the house of a brāhmaṇa, within the brāhmaṇas there was a distinction. The Sanodiyā jāti was considered to be relatively lower in status. The point is that jāti is a very significant sociological division in Indian society, and it has been so for several centuries, according to historical records.

Often in the media, the caste system is portrayed as highly discriminatory and as perpetuating injustice. However, the division of society into varṇa was, at one level, meant to engage people according to their natures. At another level, it also created a sense of community that was larger than the family. While we all need a sense of belonging and our family provides one form of that, when people who are engaged in the same profession come together, the commonality can be much stronger because they all face similar challenges.

Thus, the grouping together of jātis was intended more for the cohesion of people within the community rather than for the discrimination of that community by others. Even now, we see people group together based on shared interests. For example, there can be associations of software companies, grain merchants, construction company owners, etc. This sort of grouping of people engaged in similar professions creates a sense of belonging to a greater family—a community bigger than the family. It fosters cohesion, enabling people to learn from each other’s experiences and cope with problems collectively, rather than battling them individually.

Jāti-dharma was important in that, if we belong to a particular community, we have particular duties to that community.

Arjuna is not just speaking as an individual—he is also referring to kula-dharma. He belongs to a particular dynasty, and therefore, he has a duty to all the members of the dynasty, not just his immediate family. He also belongs to the kṣatriya community at large, and he has an obligation to the kṣatriyas (jāti-dharma). The kṣatriyas are meant to protect each other and safeguard society. So, if Arjuna does not fulfill this duty and instead participates in the destruction of the dynasty, both jāti-dharma and kula-dharma will be devastated. The active protectors of this dharma will be killed, leading to widespread disruption in society.

Today, our society faces what many have called obsessive individualism—”I first and I only.” Even families become difficult to sustain when there is excessive individualism, what to speak of communities. In this way, Arjuna is contemplating dharma at various levels—at the level of society, community, and dynasty. However, Kṛṣṇa will later discuss dharma at the level of the soul, explaining how all other forms of dharma will be taken care of when we practice dharma at the level of the soul intelligently.

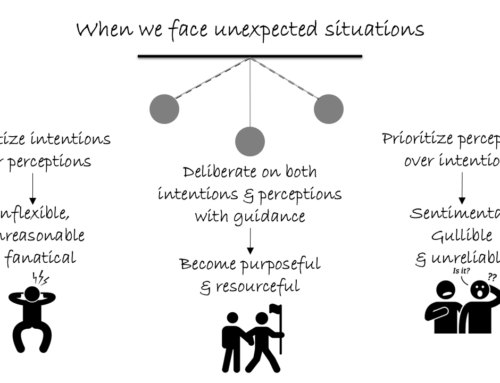

By understanding the various meanings of the word dharma, it becomes clear that here, it refers not so much to the innate nature but to the duties that facilitate social order, through which the soul’s nature can be realized. There is material dharma, which can be called apara-dharma, that maintains order in family, society, and community. Then there is sādhaka-dharma, which enables our consciousness to rise from the material level to the spiritual level. Finally, there is nitya-dharma or jaīva-dharma, as Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura would call it, which refers to the soul’s innate nature to love and serve Kṛṣṇa.

By practicing apara-dharma appropriately and engaging in sādhaka-dharma vigorously, we can realize and relish our nitya-dharma or jaīva-dharma, experiencing bliss as parts of Kṛṣṇa.

Leave A Comment