Gita 01.36 – Contemplate Contextual Karmic Considerations Before Acting (1)

Audio Link 2: https://www.thespiritualscientist.com/gita-01-36-contemplate-contextual-karmic-considerations-before-acting/

pāpam evāśrayed asmān

hatvaitān ātatāyinaḥ

tasmān nārhā vayaṁ hantuṁ

dhārtarāṣṭrān sa-bāndhavān

sva-janaṁ hi kathaṁ hatvā

sukhinaḥ syāma mādhava

Word-for-word:

pāpam — vices; eva — certainly; āśrayet — must come upon; asmān — us; hatvā — by killing; etān — all these; ātatāyinaḥ — aggressors; tasmāt — therefore; na — never; arhāḥ — deserving; vayam — we; hantum — to kill; dhārtarāṣṭrān — the sons of Dhṛtarāṣṭra; sa-bāndhavān — along with friends; sva-janam — kinsmen; hi — certainly; katham — how; hatvā — by killing; sukhinaḥ — happy; syāma — will we become; mādhava — O Kṛṣṇa, husband of the goddess of fortune.

Translation:

Sin will overcome us if we slay such aggressors. Therefore it is not proper for us to kill the sons of Dhṛtarāṣṭra and our friends. What should we gain, O Kṛṣṇa, husband of the goddess of fortune, and how could we be happy by killing our own kinsmen?

Explanation:

In this verse, Arjuna continues to explain his reasons for not wanting to fight. So far, he has questioned what pleasure could be gained if their relatives were killed. Now, he elaborates further, emphasizing that, beyond the absence of pleasure, there will be suffering as a karmic consequence for committing the sin of killing one’s own kin. This is the gist of what Arjuna describes in this verse. He says:

pāpam evāśrayed asmān: “Sin will come upon us.” The term ‘āśraya’ refers to shelter. However, ‘pāpa’ (sin) cannot offer true shelter; instead, when we come under its influence, it crushes us.

hatvaitān ātatāyinaḥ: Arjuna demonstrates his knowledge of scriptures and the codes of kṣatriyas by using the term ‘ātatāyinaḥ’, meaning ‘those whose bow is stretched.’ A bow is stretched when an arrow is placed and the archer is ready to shoot, signifying an aggressive intent and imminent attack. According to kṣatriya codes, if someone comes to kill, plunder property, abduct a wife, or set fire to a house, such aggressors are considered killable. Similarly, if someone administers poison or seizes another’s wealth, one may kill these aggressors in self-defense without incurring karmic consequences if necessary.

While Arjuna acknowledges this fact and understands it, the considerations in this situation are far from simple.

tasmān nārhā vayaṁ hantuṁ: He says that although they are aggressors, and normally killing such aggressors would not result in sin, in this case, he believes they should not be killed. “It does not befit us to kill them,” he argues.

dhārtarāṣṭrān sa-bāndhavān: He refers to the sons of Dhṛtarāṣṭra and their relatives, sa-bāndhavān.

sva-janaṁ hi kathaṁ hatvā: The term sva-janaṁ can refer to both Duryodhana’s friends and the friends of Pāṇḍavas, as their social circles often overlapped. Arjuna questions, “How can we kill our own relatives, and if we do,

sukhinaḥ syāma mādhava: what happiness will we possibly get? How will we be happy, O Mādhava?”

Here, Arjuna refers to Kṛṣṇa by the name Mādhava. He is calling out, “O lord Mādhava, how can we fight against them?” The word ‘Mādhava’ signifies the lord of the goddess of fortune. Arjuna’s question implies, “You are meant to bring good fortune to everyone, so how can you recommend a course of action that will lead to misfortune?”

It is worth noting that Kṛṣṇa has not explicitly recommended a particular course of action up to this point. However, it is understood that, until now, Kṛṣṇa and Arjuna were on the same wavelength, sharing the same intent, and were both prepared to fight. Arjuna had requested Kṛṣṇa to become his charioteer specifically for the purpose of fighting, and Kṛṣṇa had agreed. While Kṛṣṇa has not yet instructed Arjuna to fight within the context of the Gītā, Arjuna knows that fighting was their shared default position. Now, having changed his stance, Arjuna questions, “Kṛṣṇa, how can you continue to hold that position? What pleasure or happiness can come from this? What fortune can there be, O lord of the goddess of fortune? In reality, there will be misfortune. While these aggressors may deserve to be killed, our relatives deserve to be protected.”

Arjuna’s concerns are not motivated by nepotism, where one might misuse power due to affection for relatives and allow the culpable to go scot-free. That is not what Arjuna is contemplating here. His thoughts are rooted in dharma, not partiality. Arjuna reasons that taking a life is inherently wrong, but killing one’s own relatives is particularly heinous.

In this world, different types of relationships exist, but blood relationships are often the most intimate. Family and extended family typically form a vital support system, helping an individual navigate the challenges and discouragements of life. When a family, which is meant to offer support and protection, becomes an aggressor and attacker, it is a profound violation of trust and natural order. Such a situation is undoubtedly considered wrong.

A defender, whose role is to protect others from attackers, turning into an aggressor is akin to betrayal or treachery. In this case, it was indeed the Kauravas who first committed such betrayal. They were the ones who acted as traitors toward the Pāṇḍavas, and Arjuna will address this logical consideration in the upcoming verses. The significant point here is that family members are typically those to whom we feel affection and to whom we are duty-bound to provide protection—not at the expense of social justice, but rather, if it requires personal sacrifice, we should be prepared to bear that cost.

Arjuna is expressing that if we fail in our duty to protect our loved ones, our relatives, and our people, then we are failing in our responsibilities. Worse still, if we go beyond merely failing to protect them and instead attack and kill them, it becomes not just a failure of duty but a perversion of duty. Such an act is intolerable.

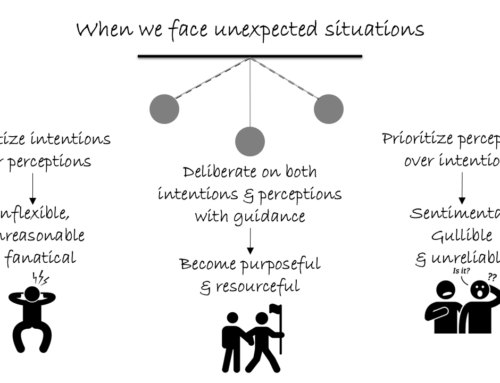

Arjuna presents compelling reasoning, but the problem lies in the limited perspective from which he operates. He is caught between his duty to his family and his responsibilities as a kṣatriya, unable to resolve the dilemma on his own. This conflict will be resolved by Kṛṣṇa, who reveals a more fundamental identity—that of the soul as a servant of Kṛṣṇa. This understanding will help Arjuna reconcile the conflict between kula-dharma (family duty) and kṣatriya-dharma (warrior duty) and enable him to choose the best course of action. The resolution and the wisdom that guide this choice will be revealed in the subsequent verses of the Bhagavad-gītā.

Leave A Comment