Gita 01.36 The Ethical Tension Between Kula – Dharma And Kshatriya – Dharma Leads To Emotional Over-Reaction And Physical Inaction

pāpam evāśrayed asmān

hatvaitān ātatāyinaḥ

tasmān nārhā vayaṁ hantuṁ

dhārtarāṣṭrān sa-bāndhavān

sva-janaṁ hi kathaṁ hatvā

sukhinaḥ syāma mādhava

Word-for-word:

pāpam — vices; eva — certainly; āśrayet — must come upon; asmān — us; hatvā — by killing; etān — all these; ātatāyinaḥ — aggressors; tasmāt — therefore; na — never; arhāḥ — deserving; vayam — we; hantum — to kill; dhārtarāṣṭrān — the sons of Dhṛtarāṣṭra; sa-bāndhavān — along with friends; sva-janam — kinsmen; hi — certainly; katham — how; hatvā — by killing; sukhinaḥ — happy; syāma — will we become; mādhava — O Kṛṣṇa, husband of the goddess of fortune.

Translation:

Sin will overcome us if we slay such aggressors. Therefore it is not proper for us to kill the sons of Dhṛtarāṣṭra and our friends. What should we gain, O Kṛṣṇa, husband of the goddess of fortune, and how could we be happy by killing our own kinsmen?

Explanation:

Arjuna continues his reasoning to explain why he does not want to fight. He says:

pāpam evāśrayed asmān: “We will be overcome by sin

hatvaitān ātatāyinaḥ: if we kill these aggressors.

tasmān nārhā vayaṁ hantuṁ dhārtarāṣṭrān sa-bāndhavān: Therefore, I feel I should not kill them.”

He concludes his argument by saying:

sva-janaṁ hi kathaṁ hatvā: “By killing one’s own people,

sukhinaḥ syāma mādhava: how can I be happy, O Mādhava?”

In every decision we make, multiple factors must be considered. For instance, when driving, sometimes the route is very clear. If we turn right, we head toward our destination; if we turn left, we move away from it. In such cases, making the right decision is relatively easy. However, if we’re traveling to a distant place with two or three possible routes showing similar estimated arrival times, the decision becomes more complex. In this situation, we may need to consider factors such as potential traffic later on. While one route currently shows a favorable time, it may become congested as we proceed, leading us to consider an alternative route.

If this makes sense, we can move on to the next step—assessing additional factors. What about traffic? If we’re on a tourist drive, are there any scenic spots along the way? Is the road smooth or bumpy? When multiple factors come into play, decision-making becomes significantly more challenging.

This is the situation Arjuna faces as he considers his duty in life. He knows the Kauravas are aggressors, and counter-aggression may be necessary if one is to move forward and attain success. Such aggressors have the potential to destroy everything, so there is nothing wrong in opposing them. In fact, it may be both right and necessary to fight against them; otherwise, they will ruin not only our lives but also the lives of those we are responsible to protect.

As a kṣatriya, Arjuna serves as a martial guardian of society, tasked with protecting his dependents. In light of this responsibility, allowing aggressors to go unchallenged would be wrong.

But then, these are ‘sva-janaṁ, sa-bāndhavān’—his own people and relatives. This brings another crucial factor into play—how can he fight against his kin? How can he kill his own family members? Arjuna faces an ethical tension between his ‘kṣatriya dharma’—his duty as a warrior to fight in battle—and his ‘kula dharma’, which calls him to protect his family and citizens. Among these two duties, which one should take precedence? Which deserves priority?

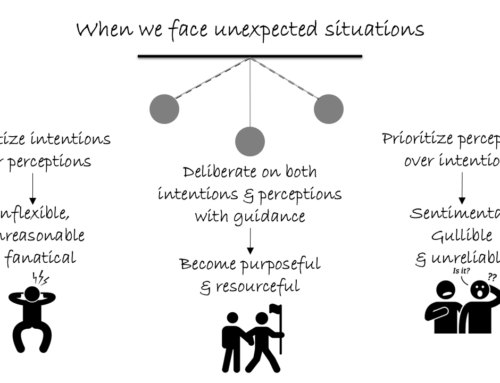

Decision-making that involves multiple factors is complex and requires calm, multifaceted contemplation. Often, we get carried away by a single factor and make a decision, only to later find that other factors carry more weight. For example, you might choose a route for its beautiful scenery. However, that scenic road may pass through a forested area with potential risks, such as wild animals or dacoits, and if your vehicle breaks down, it may be unsafe. This risk could ultimately outweigh the scenic appeal. Thus, in any situation, we must consider all relevant factors to make a balanced, thoughtful decision.

If we focus solely on one factor without considering others, our decision becomes unbalanced. Here, we see Arjuna increasingly fixated on one particular aspect: “They are my relatives”—sva-janaḥ, sva-bāndhavāḥ. These terms appear twice, and throughout this section, they recur frequently. This repetition reflects the dominant influence these thoughts have on Arjuna’s mind, skewing his analysis in that direction. The fact that they are his relatives is, of course, important, and undoubtedly, we would want to avoid conflict with our own family.

Family conflicts can be particularly nasty because the emotions involved are so strong. When we care deeply for someone, and they let us down, the disappointment can be overwhelming, leaving us feeling powerless. This is why it’s essential to adopt a holistic view of the situation, one not clouded by immediate emotions. Emotions that arise in the moment often distort our perception, tilting our vision in one direction. As a result, we may only see things in a particular way, while other aspects—though visible—fail to register in our consciousness. What registers dominates our attention, while what doesn’t is easily overlooked. With such a skewed vision, we risk making choices that ultimately harm us and worsen the situation. To avoid this, we need to carefully consider our actions and strive for a balanced decision.

Leave A Comment