Gita 01.29 – The inner attack of emotions does what no outer attack of enemies could have done

vepathuś ca śarīre me

roma-harṣaś ca jāyate

gāṇḍīvaṁ sraṁsate hastāt

tvak caiva paridahyate

Word-for-word:

vepathuḥ — trembling of the body; ca — also; śarīre — on the body; me — my; roma-harṣaḥ — standing of hair on end; ca — also; jāyate — is taking place; gāṇḍīvam — the bow of Arjuna; sraṁsate — is slipping; hastāt — from the hand; tvak — skin; ca — also; eva — certainly; paridahyate — is burning.

Translation:

My whole body is trembling, my hair is standing on end, my bow Gāṇḍīva is slipping from my hand, and my skin is burning.

Explanation:

Here, Arjuna continues to describe his reaction to the imminent war about to take place between relatives:

vepathuś ca śarīre me: “My whole body is trembling.”

roma-harṣaś ca jāyate: “My hair is standing on end.”

gāṇḍīvaṁ sraṁsate hastāt: “My bow, Gāṇḍīva, is slipping from my hands.”

tvak caiva paridahyate: “My skin is burning.”

The emotional and the physical are intimately related. When we experience strong emotions, they manifest physically. On a gross level, when we are heartbroken, we may cry; when we are happy, we may laugh. These are physical reactions to, or expressions of, emotions. Similarly, in times of great grief, horror, or shock, certain physical responses occur. Later, it will be mentioned that Arjuna’s eyes are also filled with tears.

But here, the most significant aspect of Arjuna’s reaction is the slipping of the Gāṇḍīva bow. Why is this so significant? For a warrior, the weapon is almost like a part of the body. It’s not merely an external object to be carried—it defines the warrior. The weapon is where the warrior excels and demonstrates his skill. Thus, for a warrior, the weapon becomes like a bodily limb. Just as one would never give up a limb unless severed by some terrible assault, similarly, a warrior almost never relinquishes his weapon. Yet, here we see Arjuna letting go of his bow.

The gravity of the situation—with Arjuna’s bow slipping aside—is further highlighted by the fact that he had taken a vow never to abandon his Gāṇḍīva and never to put it aside when confronted with aggressors—unless faced by brāhmaṇas, Viṣṇu, or devotees of Viṣṇu. Crucially, no hostile enemy would ever cause him to relinquish his Gāṇḍīva. This vow was so strong that on the seventeenth day of the war, when Yudhiṣṭhira Mahārāja had been defeated, wounded, and humiliated by Karṇa, he retreated to his tent to recover. His solace was the certainty that Arjuna would kill Karṇa and avenge his humiliation. However, when Arjuna visited Yudhiṣṭhira before confronting Karṇa, Yudhiṣṭhira was furious, outraged, and hurled harsh words at Arjuna, condemning him. One of his accusations was: “What is the use of your Gāṇḍīva bow if you haven’t killed that sūta? Better give your Gāṇḍīva to Bhīma or someone else, and they will do the work of killing Karṇa.”

Now, Yudhiṣṭhira was a venerable elder brother to Arjuna, and Arjuna respected him deeply. He did not speak against Yudhiṣṭhira, even when he blundered terribly in the gambling matches—losing everything, enslaving himself and his brothers, and even summoning and disrobing Draupadī. Throughout it all, Arjuna remained silent. One might say that he was silent in the presence of Bhīma, but the truth is that Arjuna was so bound by his vow that he could never put aside his bow. He felt it impugning his honor that someone had asked him to do so, and he raised his sword to attack Yudhiṣṭhira for having insulted him in this way.

It was only because of Kṛṣṇa’s timely intervention that the situation was resolved. Kṛṣṇa explained how vows are contextual and expertly addressed the issue, suggesting that Arjuna could dishonor Yudhiṣṭhira, as dishonor is akin to death for an honorable person. Then, Kṛṣṇa advised Arjuna to praise himself, thereby settling the entire situation.

The point here is that for a kṣatriya, there is no need to be squeamish about performing his duty, even if it involves fighting to defend. Of course, they should not be indiscriminate. The responsibility of protection should be entrusted to those who are capable and sensitive enough to understand that, while violence is not inconsequential, it should never be used as a first resort. However, for martial protectors of society, violence is a fact of life. In the face of violence, kṣatriyas cannot afford to be squeamish.

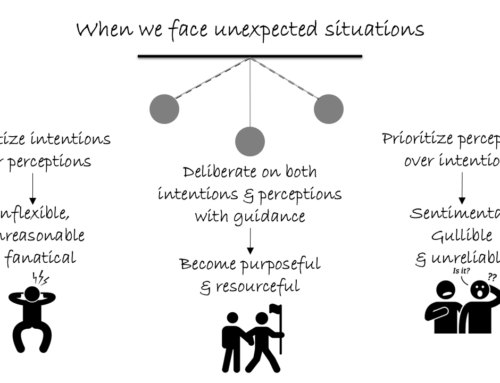

Yet, here we see Arjuna, whom no external enemy could make put down his bow, is overwhelmed by an internal enemy—the agony of facing a war in which his own relatives would be involved. This overpowering emotion completely shook him to the core, as evidenced by his description of his Gāṇḍīva bow slipping from his hand, indicating that he is terribly overwhelmed. A kṣatriya is not afraid of wounds, blood, or even the greatest and most dangerous enemies. Yet, even such a kṣatriya can be consumed by inner confusion and emotional turmoil.

The wisdom of the Gītā that enables Arjuna to withstand and counter this emotional assault will be discussed in the later narrative of the text.

Thank you.

Leave A Comment