Gita 01.27 – Undiscerning Visual Perception Erodes Spiritual Conviction

Audio Link 2: https://www.thespiritualscientist.com/gita-01-27-undiscerning-visual-perception-erodes-spiritual-conviction/

tān samīkṣya sa kaunteyaḥ

sarvān bandhūn avasthitān

kṛpayā parayāviṣṭo

viṣīdann idam abravīt

Word-for-word:

tān — all of them; samīkṣya — after seeing; saḥ — he; kaunteyaḥ — the son of Kuntī; sarvān — all kinds of; bandhūn — relatives; avasthitān — situated; kṛpayā — by compassion; parayā — of a high grade; āviṣṭaḥ — overwhelmed; viṣīdan — while lamenting; idam — thus; abravīt — spoke.

Translation:

When the son of Kuntī, Arjuna, saw all these different grades of friends and relatives, he became overwhelmed with compassion and spoke thus.

Explanation:

Arjuna beholds his various relatives, across many generations, gathered to fight.

tān samīkṣya sa kaunteyaḥ: When the son of Kuntī (Arjuna) saw

sarvān bandhūn avasthitān: all his kinsmen, related to each other in various ways, present there,

kṛpayā parayāviṣṭaḥ: he became overwhelmed with compassion

viṣīdann idam abravīt: and, lamenting, he thus spoke.

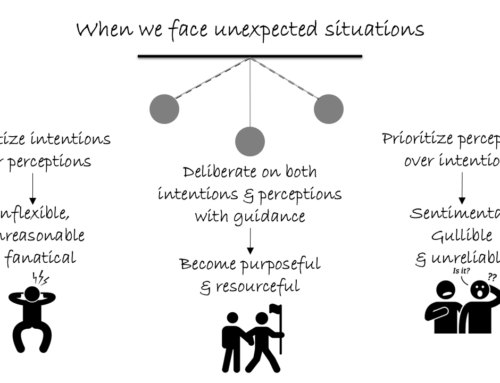

Here, the effect of undiscerning visual perception is being depicted. Undiscerning visual perception means that we see with our eyes, but if we don’t use our intelligence to carefully process what we are seeing, we can be led astray by illusion. This is precisely what happens to Arjuna. When he first sees the various warriors, his initial perception—depicted in the earlier verse—was that he wanted to see those fighting on the side of the evil-minded son of Dhṛtarāṣṭra. At that time, his perspective was that this is a war between good and evil, and those who have sided with evil must be punished. Thus, his vision was more firmly rooted in reality. He saw the Kauravas as vicious, Yudhiṣṭhira as virtuous, and Kṛṣṇa as the Lord of virtue—he was fighting on their behalf.

However, now that his undiscerning visual perception has distorted his conceptions, he no longer sees them as those who have sided with evil but as his relatives. He will subsequently argue, “How can I kill my relatives?” ‘Kṛpā’ means mercy, but here ‘kṛpayā’ refers not to mercy but to compassion. It denotes the emotion experienced by one who is the dispenser of mercy. So, ‘kṛpayā’ compels one to show ‘kṛpā.’

For example, if a beggar is in a very destitute condition—hands and legs amputated, appearing skeletal, extremely hungry, and pitiable—such a sight may invoke ‘kṛpayā’ (compassion) in a passerby. This compassion might prompt the passerby to show ‘Kṛpā’ by giving charity. Similarly, when Arjuna sees all these warriors assembled on the battlefield, about to engage in a brutal, bloody conflict where many will fight to the death, he becomes overwhelmed with compassion. He begins to wonder whether his relatives truly deserve to fight and kill each other in such a manner, leading him to have overwhelming second thoughts about the inevitable conflict. He starts lamenting, thinking, “Oh! Such a thing should not happen. This fight should not take place.” This is the mindset that leads him to speak the words that follow.

The first chapter of the Bhagavad Gītā is known by different names, with two prominent ones used by commentators: ‘Sainya-nirīkṣa-yoga’ and ‘Arjuna-viṣāda-yoga.’ This verse marks the transition between these two topics. Until verse 26 or 27, the focus is on observing the armies (‘sainya-nirīkṣa’). First, Duryodhana observes the armies on both sides, followed by the events that occur while the conches are being blown, which are narrated by Sañjaya as he reports them to Dhṛtarāṣṭra. Then Arjuna performs ‘sainya-nirīkṣa.’ He first expresses his desire to observe the armies, which is described from verses 20 to 23. The actual observation Arjuna undertakes and its subsequent effect are detailed from verses 24 to 26.

When Duryodhana talks about his ‘sainya-nirīkṣa,’ he does not speak in terms of relatives and friends. Duryodhana’s mind is so consumed by greed that it has destroyed any affection based on relationships, which is why he never refers to the Pāṇḍavas as his brothers. In his description of the warriors on both sides, he speaks only in terms of their prowess: “Oh, this is a great warrior, he is like this, and we also have great warriors.” There is no mention of any relationships.

Does this mean he has transcended bodily affection and attachment? No, not at all. There are actually three levels: the level of bodily attachment, the level of spiritual vision and attachment that transcends bodily attachment, and the level of material greed that also destroys bodily attachment—not by making a person unattached, but by making them so attached to material things that they are willing to sacrifice even their bodily relationships for them. For example, in Indian history, Aurangzeb, in his quest for the throne after Shah Jahan, imprisoned his own father and killed his own brother, Dara Shikoh.

Similarly, it is not that Duryodhana was particularly spiritual; rather, he was so greedy that he lost even basic human civility in terms of showing respect and regard for his relatives. If we consider these three levels, such material attachment and greed—where one doesn’t even care for relationships—represent the lowest level exhibited by Duryodhana. The second level involves attachment to material relatives based on a sense of duty. The highest level is spiritual attachment to Kṛṣṇa, where one does not become indifferent to material relationships but subordinates them to our spiritual relationship with Kṛṣṇa.

We could categorize these as adharma, aparadharma, and paradharma. Duryodhana is at the level of adharma, Arjuna is at the level of aparadharma, and Kṛṣṇa’s instructions through the Gītā will elevate Arjuna to the level of paradharma.

The concerns expressed by Arjuna are not wrong. To care about one’s relatives and to be concerned about not wanting unnecessary bloodshed—especially the bloodshed of one’s own kin—is commendable. Compared to irreligion, material religiosity is beneficial because it helps maintain order in society and encourages people to act in relatively less selfish and more selfless ways. Thus, aparadharma is necessary for maintaining societal order, but there are cases where paradharma is required.

Arjuna’s soft-heartedness here is not necessarily a weakness. Rather, it becomes a weakness only when that soft-heartedness leads him away from his duty toward Kṛṣṇa at the level of paradharma. We will explore Arjuna’s character further in subsequent verses, but the central theme here is that undiscerning visual perception can distort our spiritual convictions.

Thank you.

Leave A Comment