Gita 01.21 The non-partisan position of the Gita’s revelation points to its universality

Audio Link 1 : https://www.thespiritualscientist.com/gita-01-21-the-non-partisan-position-of-the-gitas-revelation-points-to-its-universality/

arjuna uvāca

senayor ubhayor madhye

rathaṁ sthāpaya me ’cyuta

yāvad etān nirīkṣe ’haṁ

yoddhu-kāmān avasthitān

Word-for-Word:

arjunaḥ uvāca — Arjuna said; senayoḥ — of the armies; ubhayoḥ — both; madhye — between; ratham — the chariot; sthāpaya — please keep; me — my; acyuta — O infallible one; yāvat — as long as; etān — all these; nirīkṣe — may look upon; aham — I; yoddhu-kāmān — desiring to fight; avasthitān — arrayed on the battlefield.

Translation:

Arjuna said: O infallible one, please draw my chariot between the two armies so that I may see those present here, who desire to fight, and with whom I must contend in this great trial of arms.

Explanation:

This verse introduces the first words spoken by Arjuna, who has a specific request for Kṛṣṇa:

senayor ubhayor madhye rathaṁ sthāpaya me ’cyuta: “Please place my chariot in between the two armies.”

What is the purpose of this request? Arjuna clarifies:

yāvad etān nirīkṣe ’ham yodhukāmān avasthitān: “So that I can observe those assembled here, eager to fight in this war.”

It’s interesting that this question reveals much by what it doesn’t say and by what it implies. At this stage, after extended battle plans have reached their climax, the moment for action has arrived. And in this critical moment, Arjuna’s desire to observe not the military formations, but the opposing warriors themselves, is intriguing.

At the start of the Bhagavad-gītā, when Duryodhana sees the Pāṇḍava warriors assembled on the battlefield, his focus is on their military formation. He evaluates their arrangement, which prompts him to take action by approaching Droṇācārya and urging him to fight wholeheartedly on his behalf.

The point is that Duryodhana is focused on strategizing the best way to engage in battle. Therefore, upon seeing the aggressive military formation of the Pāṇḍavas, he feels the need to ensure that his own side is equally prepared and formidable.

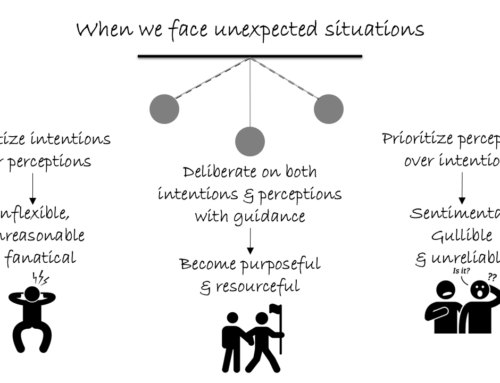

However, Arjuna’s question is not about the opponents’ martial arrangement or battle strategies. Rather, he is concerned with understanding their psychological disposition and inner intentions. His question is—who are the ones assembled here to fight with me? (kair mayā saha yoddhavyam).

We’ll see that his question spans three verses. In this verse, he says—yāvad etān, by which I can observe (nirīkṣe ’ham) those who have gathered with the intention to fight (yodhukāmān avasthitān).

Thus, he requests to be positioned senayor ubhayor madhye—in the middle of the two armies. Although he is on the Pāṇḍavas’ side and is their foremost archer, he asks to move between the two armies for this purpose.

Consider a game like kabaddi, where the two teams are arrayed on opposite sides. Suddenly, one of the chief players from one side says, “I want to go into the middle to see who is there.” At one level, we might say that being in the middle offers a clearer view. However, the middle is not the place to be. Once the battle lines have been drawn, each player must choose a side.

Generally, those who don’t take a side are referred to as fence-sitters. Of course, some individuals can act as mediators, facilitating dialogue between two conflicting parties with the intention of bringing them together. Then, there are bench-sitters who do not play at all. However, fence-sitters are those who are unwilling to commit and unable to decide what to do.

For someone to step into the middle just as a battle is about to begin is, at the very least, a disorienting action. Once the battle lines are drawn, the middle is not a safe place to be. Each warrior must be positioned on their side, in their appropriate place. Thus, positioning oneself in the middle carries significant implications.

The Bhagavad-gītā is spoken on middle ground. It is when Arjuna is positioned between the two armies that Kṛṣṇa delivers the teachings of the Gītā. This setting indicates that while there may be conflict at an earthly level, and actions may seem partisan, the Gītā’s positioning reflects its non-partisan stance in a partisan conflict.

Non-partisan means impartial, non-sectarian, or universal. In fact, Kṛṣṇa’s message is universal. It is intended not just for the Pāṇḍavas, but also for the Kauravas. It is not limited to any particular denomination—be it a specific religion, region, gender, or social class—rather, it is meant for everyone.

The non-partisan location of the Gītā’s revelation—the fact that it is spoken in the middle of the two armies on the battlefield, on neutral ground—highlights its transcendence, universality, and the universal nature of its spirituality. This message did not benefit only Arjuna—if Duryodhana had been willing to hear it, he too could have gained from it.

God does not take sides in human conflicts—it is humans who choose to side with or against God.

The Bhagavad-gītā categorically tells us that Kṛṣṇa is the Lord of everyone, as expressed in the phrase ‘suhṛdaṁ sarva-bhūtānāṁ’—the well-wisher of all living beings. However, not all living beings share a similar disposition toward Him. While He is non-partisan, He is also purposeful, aiming to do good for everyone. Accordingly, He acts in ways that reflect this purpose. Some people are allies, while others are not.

In a mental asylum, where patients have varying levels of illness, the doctor serves as the well-wisher of all patients in the mental health care center. However, if some patients become violent, threatening, and destructive, endangering others, and if other patients attempt to restrain them, the doctor must take action.

When the doctor intervenes, it is not a matter of taking sides in the conflict among patients. Rather, the doctor’s role is to ensure the well-being of all patients. Nonetheless, the doctor will prioritize whom to focus on to restore order in the facility, ultimately benefiting everyone.

‘Paritrāṇāya sādhūnāṁ vināśāya ca duṣkṛtām’—Kṛṣṇa empowers the virtuous and disempowers the demonic, the vicious, and those opposed to God. This is not sectarianism; it is an action aimed at restoring order—both social and spiritual. Through the establishment of dharma, everyone will ultimately benefit.

When individuals in a mental asylum exhibit violent behavior, restraining or sedating them is done for their own good; otherwise, they would cause significant disruption and destruction for everyone involved. Ultimately, if they succumb to their fits of insanity, their condition will worsen. Thus, they need to be restrained for their own well-being.

Similarly, while the Gītā’s message encourages Arjuna to gain a transcendental vision through which he will fight, the fighting itself is not sectarian. It is universal, aimed at benefiting all. More importantly, Kṛṣṇa’s message is not solely about fighting a war—it is about learning to live in harmony with dharma. This message resonates with and benefits everyone.

Thank you.

Leave A Comment